Cities have been synonymous with development, but climate change and, now, the Covid-19 pandemic have revealed the systemic vulnerabilities of urban areas. To secure a more sustainable future, write Christopher H Lim and Tan Ming Hui of the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, a rethinking of development strategy and planning beyond the traditional economic- and city-centric world is essential, especially in the Global South.

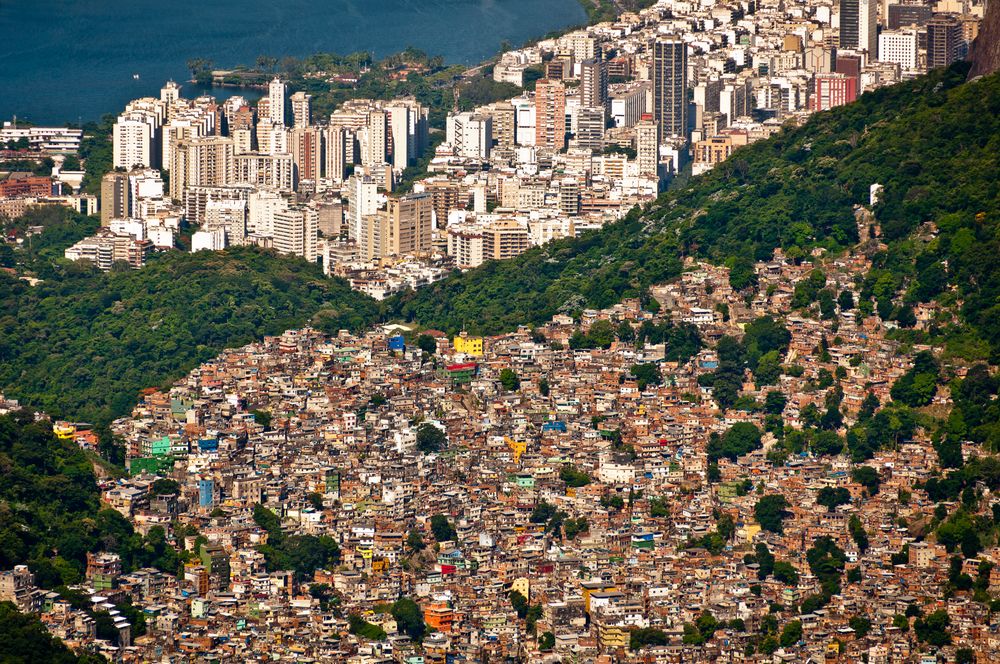

Wealth divide in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: With social distancing impossible, city slums can become hotbeds for viral infection (Credit: Donatas Dabravolskas / Shutterstock.com)

When the war against Covid-19 is behind us, many developing countries in Asia, Latin America and Africa will understandably rush to seize opportunities to rebuild their countries and economies, seeking development loans and technical support from global institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Asian Development Bank (ADB), Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and World Bank to rejuvenate their economies, potentially accelerating the rate of global urbanization. But is urbanization the best way forward?

The driving forces of urbanization

Historically, the growth of cities is closely associated with development and modernization. Ancient cities such as Rome served as political and financial centers, spawning trade routes and networks. In medieval Europe, fortified towns or cities emerged around castles – the seats of power and bureaucracy.

Today, cities remain the drivers of economic growth in both developed and developing countries. The first and second industrial revolutions resulted in cities becoming the centers of industrialization and productivity. Cities depend heavily on economies of scales to create productivity and cost advantages for investors and can distribute scarce resources and services to a large population in a short period of time.

After World War II, starting with Japan, many developing Asian countries transformed themselves with a single focus on economic prosperity. Based on the flying geese model, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore joined the pack in the early 1980s. China has also embraced a similar developmental dogma.

In the 1960s, the development and introduction of high-yielding wheat varieties by Norman Ernest Borlaug, combined with modern agricultural production techniques, addressed global food security problems and greatly reduced the need for farm labor. This Green Revolution meant that the excess of young workers from rural areas provided a constant supply of manpower in urban areas.

Over the next three decades, globalization and a preoccupation with increasing shareholder value resulted in efficiency and productivity (often termed “competitiveness”) becoming the central theme in our economic model. The confluence of global political and economic events in the 1990s also facilitated the rise of globalization and capitalism, including the Shanghai Stock market reopening in 1990 for the first time since 1949, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) among the United States, Canada and Mexico concluded in 1994 (and renegotiated in 2017-18, with the new US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, going into effect in July 2020).

Today, cities provide ideal environments to drive innovation, attracting young technocrats from all over the world – proximity and opportunities for interaction are deemed necessary to foster creative ideas and inventions. For individuals, rural-to-urban migration has been synonymous with upward mobility. Urban areas offer the economic appeal of job opportunities, poverty alleviation, and quality of life. Globalization has also led to the movement regionally and worldwide of migrants – often from rural to city, and from city to city.

In 2008, the number of people living in urban areas exceeded those in rural areas: Over half of the world’s population now lives in urban areas, and urbanization is set to increase to 68 percent by 2050. Many urban areas in the developing world have grown into megacities. In 1950, New York and Tokyo were the only two megacities, but by 2018, 31 others had joined the list. In the same year, China launched a plan to develop 19 super regions. The United Nations predicts that 10 more megacities will emerge by 2030.

Urban challenges

Cities, however, are vulnerable to future pandemics and climate change, with greater urbanization driving greater inequality and all the social ills connected to a widening income divide. This highlights a need for a new developmental model, different from the economic-centric, city-centric world pattern, especially for the global South and its fast-growing populations.

In the age of Covid-19, given their density, large cities are plainly not ideal environments for social distancing. Megacities such as New York, London and Madrid have been among the hardest hit in their countries. Many urban areas in developing countries, including Mexico City and Manila, are known for slums with crowded living conditions and a lack of clean water and adequate sanitation that could easily become hotbeds for infection.

In the urban sprawl, there are key challenges to consider:

Antimicrobial resistance With the unprecedented economic growth of cities in low- and middle-income countries, an increasing number of people in India, China, Latin America and Africa are changing their diets to include more meat and dairy products. To meet the increasing demand, industrial animal farming with an excessive and indiscriminate use of antimicrobials to enhance profits has become the norm. From 2000 to 2018, there was a clear indication of escalating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in animals in these countries. By 2050, AMR could contribute to the deaths of 10 million people a year. The rise of antimicrobial resistance could mean that future pandemics will be harder to treat.

Failure to contain the community spread of diseases could also negatively affect the long-term health of a sizeable percentage of the population. Covid-19 is known to cause multi-organ damage, and at least 40 percent of those who are infected are expected to suffer from lasting health complications such as persistent pulmonary damage, post-viral fatigue and chronic cardiac issues. This would translate into heavy costs for taxpayers and a greater burden on healthcare resources including caregivers.

Due to the disproportionate contributions that metropolitan areas make to their countries’ economies, lockdowns due to public-health crises are costly and can increase sociopolitical tensions, not to mention the challenge of implementing effective and restrictive public-health measures in densely populated areas.

Inequality In the megacities of the global South, unequal distribution of wealth, population, level of social-physical development and political influence is common. From the perspective of risk diversification, the reliance on megacities for driving economic growth is unsustainable, especially in the event of future natural or man-made disasters, including pandemic outbreaks, climate-related calamites, and cyber or terrorist attacks.

Large cities such as New York, Paris, Tokyo and Hong Kong are among the world’s most expensive places in which to live. High-density metropolitan areas face a host of other problems, including higher crime rates, greater incidence of poverty, homelessness, and public-health threats including stress and mental illness.

Lessons of Covid-19

Over time, the robustness of economic activities in cities has become key to the survival and progress of both developed and developing countries. While urbanization was a driving force for economic development and growth in the past, difficult and worsening challenges suggest that the development of new cities and megacities may not be the best option for the future.

Covid-19 has destabilized the foundation of the megacity economy. Socio-economic activities such as shopping and education are moving into cyberspace. Medical consultations have also shifted online, with patients logging in from home.

With the changing face of the economy in the post-Covid-19 era, the decentralization of business activities away from the city centers, living in rural-plus areas or in small townships could become more attractive options. These townships should be supported by a high-speed digital network powered by renewable energy whenever possible.

Having most of the population living in small townships would make isolating during pandemics easier. Another logistical advantage would be the relative ease of rescuing and relocating residents in times of disasters. Other benefits include reduction in crime and the reduction or elimination of slums and the prevention of such pockets of poverty from forming. Sustainable food security could be implemented through the cultivation of agricultural products using digital and precision farming. Finally, it would also be easier to promote social cohesion in smaller communities.

For individuals, housing costs would be greatly reduced, and there would be significant improvement in work-life balance due to the shift of corporate culture to remote working, which would reduce stress from the daily commute. These lifestyle changes would allow for more family time, physical exercise and sleep.

While the search for the Covid-19 vaccine continues, it would be timely and wise for policymakers and international development agencies to anticipate, develop and explore new growth strategies for vulnerable developing countries in the post-pandemic age. This crisis provides a window of opportunity to review and update our economic models and processes to keep up with the conditions and opportunities of the 21st century. With a fresh outlook on how we live and work, humans may no longer have to be caught in the daily dilemma between economic livelihood and the long-term wellbeing of our species.

Further reading:

Christopher H Lim

S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU)

Tan Ming Hui

S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU)

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.