The recent altercation in the South China Sea between Chinese vessels and Philippine ships underscores the urgent need for science diplomacy and cooperation in fisheries management to bring calm to the tense waters, Rodger Baker of the Stratfor Center for Applied Geopolitics at RANE and James Borton of the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University argue. To make their case, they share the results of a survey of scientists, analysts and security professionals in the region and highlight examples of maritime cooperation around the world.

Calm waters off Vietnam: At the heart of this long-running regional row over maritime space are resources, chief among them fisheries (Credit: Frank Fischbach / Shutterstock.com)

On August 5, Chinese and Philippine vessels were involved in a tense face-off in in a disputed area of the South China Sea near the Second Thomas Shoal, a formation occupied for decades by Filipino military based in a rusting grounded navy ship. Two days later, Philippine officials presented to media videos and photographs showing six Chinese Coast guard and two militia ships blocking two chartered civilian boats carrying supplies to the Philippine forces stationed on the shoal. At one point, the Chinese trained a powerful water cannon on one of the supply craft. The Philippine government summoned the Chinese ambassador in Manila to lodge a strong protest. The US, the European Union, Australia, Canada and Japan issued statements in support of the Philippines.

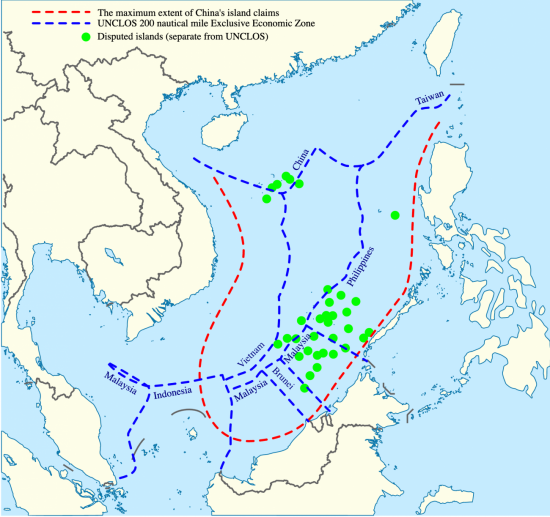

This latest encounter between China and one of its main rival claimants in the maritime dispute in the South China Sea, which Filipinos call the West Philippine Sea, is another reminder of the potential for conflict in the area, especially as the US and its allies and partners – including countries from outside East Asia – have been asserting the freedom of navigation by traversing waters that China considers to be its sovereign territory. The South China Sea is regarded as a possible flashpoint that might turn the intense China-US strategic competition into a hot conflict.

In considering the longstanding quarrel among the six parties involved, it is important to understand that at the heart of this regional row are resources, chief among them neither oil nor gas nor seabed minerals, but fisheries. Yet political tensions and the territorial disputes have marred efforts to establish effective regional fisheries management. The biggest issues: overfishing; illegal, unlicensed and unreported (IUU) fishing; habitat destruction; and environmental change, all of these problems having international implications.

Our recent survey of scientists, analysts and security professionals across the region made clear the link between human security priorities – the environment and food – and traditional security. By engaging with both scientists and security and policy professionals, we aim to promote more meaningful discussions that can bridge the divide between geopolitical competition and the need to tackle regional and global issues that are beyond the ability of any single country or government to handle.

Respondents generally emphasized the importance of scientific research, data collection and dissemination, as well as how critical it is to take into account science-based inputs (evidence) in the policy sphere as a key factor both to manage fisheries and to influence broader strategic decisions. While scientific cooperation and science diplomacy will certainly not resolve the complex regional differences, they are necessary channels of communication and trust-building that not without historical precedent.

Almost 75 percent of respondents to our survey agree that there is an environmental security crisis in the South Chia Sea due to overfishing. Their assessments indicate that the region is at this tipping point because of decades of fishing exploitation. With half of the world's fishing vessels operating in these contested waters, this is no surprise. Survey respondents were almost unanimous in their view that unchecked fishing practices are a major threat to future fisheries sustainability.

This is what has been called the tragedy of the commons and is playing out before the world. Respondents to our survey strongly support the idea that cooperation is the only way forward to addressing the “softer” challenges such as the urgent need for fisheries management and marine science research. In countries around the region, the designation of marine protected areas (MPAs) are critical to supporting biodiversity and sustainability for marine life. While geopolitical wrangling and foreign policy driven by nationalism may limit the benefits of such cooperation, there is cautious optimism that the need for better data across the region and the urgency of the environmental crisis would allow space for expanding scientific collaboration – an obvious requirement for more informed policy decisions.

With coral reefs already in peril as a result of the unfolding ecological disaster in once fecund fishing grounds, there is a clear imperative – a social responsibility – to turn the South China Sea from a body of water that divides to a maritime space that unites. As reclamation damages natural habitats, agricultural and industrial waste poisons the ocean, and overfishing severely reduces fish stocks, the voices of marine biologists are ever more vital in pursuing a rules-based ecological approach to safeguard the environment and deal with the threats to endangered species such as sea turtles, sharks and giant clams.

There are indications that countries in the region understand this, however heated their debates over boundaries may be or however slow they have been in resolving those differences. In December 2021, China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations endorsed the China-ASEAN Plan of Action on a Closer Partnership of Science, Technology and Innovation from 2021 to 2025. This was an encouraging development as the parties agreed to explore sustainable science-driven cooperative mechanisms. This blueprint and under-the-radar marine environment-focused forums and workshops are shaping a new South China Sea narrative about addressing the ecological dangers of biodiversity loss, climate change, coral reef depletion, pollution and collapsing fisheries.

While Beijing and ASEAN member states recognize the challenges, political and security trends continue to weigh against rapid breakthroughs in cooperation and concerted multilateral action. Yet, there are valuable historical models for international oceanic collaboration, even among states that are in no way allies or even partners. Take the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) tectonics drilling surveys conducted in 2014 among scientists from the United States, Japan, China, South Korea, Australia, India and Brazil in the South China Sea. Consider too the South China Sea Monsoon Experiment (1996-2001), initiated by China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, which brought together scientists from Taiwan (yes, Taiwan), Australia and the US. Another example: the Joint Oceanographic Marine Scientific Research Expeditions conducted between the Philippines and Vietnam in the South China Sea (JOMSRE-SCS) from 1996 to 2007. Manila and Hanoi are resuming this joint initiative.

Judging from our survey, marine scientists and policy experts are convinced that the best way to engage in effective ocean science cooperation is to pursue common interests across the region – the need to understand and deal with climate change, ocean acidification and severe weather patterns such as the increasing number of typhoons, and to explore jointly the benefits of marine protected areas, with a practical eye to conserving vital fisheries and preserving access to maritime food resources for future generations.

Science diplomacy is not a new approach to international relations. The time has definitely come for the approach to be adopted in dispute management in the South China Sea, especially given what appear to be more frequent and dangerous maritime run-ins such as the Second Thomas Shoal clash. Ocean science has in the past been adopted in other parts of the world as a diplomatic tool for peacebuilding since scientific evidence informs negotiations and fosters joint marine research and capacity building.

The Mediterranean Sea coast runs from the Atlantic Ocean to the western edge of Asia and separates Europe from Africa. Like the South China Sea, it has had its share of conflicts, including the longstanding Israel-Palestine conflict. The Mediterranean Action Plan, adopted by countries in the region and the European Community in 1975, offers a regional monitoring network and the underpinning legal instruments to protect the region from environmental exploitation. The mechanism has been effective in catalyzing cooperative efforts among the subscribing countries.

The Arctic Council is a forum that highlights how scientific collaboration in a contested area can proceed without much hindrance from traditional security disputes. The eight Arctic Council members include the US and Russia, intense geopolitical rivals, and indigenous groups. China has been an observer since 2013. Council members have concluded several legally binding agreements to promote environmental protection and sustainability, including an accord to enhance scientific cooperation that was signed in May 2017. The Arctic Council, however, has not always been a successful platform for collaboration and may be a cautionary tale of the limits of capacity-building approaches. The failure to manage geopolitical tensions in recent years has raised questions about the effectiveness of the grouping and the possibility of any meaningful collaboration in future.

The convergence of science and geopolitics has necessitated the expansion of scientific fora and collaborative problem-solving efforts among neighbors. At times, scientific collaboration may operate in ways that defy entrenched strategic rivalries – the US-USSR space cooperation during the Cold War is a shining example. But just as policy makers need to be mindful of the scientific information in shaping their policies, so too must scientists be more aware of the geopolitical realities that affect (narrowing or expanding) the space for collaboration and cooperation. The Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated that the mixing of science and geopolitics can actually divide countries and people, including traditional allies, and even make international interaction toxic or highly politicized.

Nevertheless, science diplomacy offers the opportunity for building trust in the South China Sea. It can be an effective in calming the disputed waters and giving much needed space for meaningful negotiations on important issues such as fisheries management, the access and development of other valuable resources, and pressing environmental concerns. But in the end, it is the political leaders not the scientists who will have to commit to preserving the peace for the long term.

Further reading:

Rodger Baker

Stratfor Center for Applied Geopolitics at RANE

James Borton

Foreign Policy Institute, School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.