Following the conclusion of the 2020 Olympic Games, historian Xu Guoqi of The University of Hong Kong reflects on Japan’s history with the Olympics, possible implications of Tokyo 2020 on Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympic Games, and the future of China-US relations.

Fierce competition: At the delayed 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, China led the gold medal race until the final day when the United States pulled ahead by one (Credit: David McIntyre/DGM Photography)

Tokyo was chosen to host the Olympiad three times. The first one was supposed to take place in 1940, after the Japanese launched an all-out effort to win the honor to host the Games in the early 1930s. Its convincing – and winning – argument then was that the Olympic movement was supposed to be international by nature and design. But the Games had never taken place outside the United States and Europe. Japan was qualified and reasoned that it should be chosen as the first non-Western to host. Indeed, the Asian nation was a major world power by the end of the World War I. The brilliant performances of Japanese athletes at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games showed the International Olympic Committee (IOC) that Japan was a force in sports as much as it was a global player.

Playing the internationalization card was one thing, but Japan’s real intention to host the Games was nationalistic. The country suffered one of the worst earthquakes in 1923, which caused enormous damage to the city of Tokyo and the surrounding areas. By the early 1930s, Japan wanted to show the world that not only could it rebuild itself but it would be more advanced and beautiful than ever. Nothing was more effective than the Olympic Games to draw tourists to experience and witness the re-emergent Japan. Another equally important reason for Tokyo’s eagerness to host the 1940 Games was to celebrate the 2,600th anniversary of Japanese Empire. Crowning such a grand jubilee with a spectacular Olympiad would underscore Japan’s unique and glorious history.

Japan was awarded the honor to host 1940 Olympic Games during Nazi Germany’s Berlin Olympic Games in 1936. But the 1940 Games never took place: Japan forfeited the rights to host in 1938 because it was by then in an all-out war with China. In my recent book, Asia and the Great War: A Shared History, and other publications I have written that Japan and China have had a long and shared history. Tokyo’s disastrous first Olympic Games in 1940 was a clear example.

China’s first participation in the Olympics had a strong connection with Japan. China had not planned to send any athletes to the 1932 Los Angeles Games. It was only when the media reported that Manchukuo, the puppet state Japan established in 1932 after its occupation of an area in northeastern China, planned to send competitors to Los Angeles to legitimize Japan’s invasion of China that the Chinese decided to participate. In the end, they sent only one athlete, a reminder that the Republic of China still existed. Forty years later, Japan would use sport to foster international relations in a positive way, playing an instrumental role in setting up the “ping-pong diplomacy” between the US and the People’s Republic of China. In 1971, Japan hosted the world table tennis championship and persuaded Beijing to take part.

The three Olympiads awarded to Tokyo offer several points of contrast and continuity. The 2020 Olympics may well have been as “cursed” as the cancelled 1940 Games, but they were postponed a year not abandoned. Covid-19 was a challenge not of Japan’s own doing and was beyond its control. The 1940 and 2020 Games were intended to demonstrate Japanese resilience, scheduled as they were some years after devastating earthquakes in 1923 and 2011.

The host’s intentions for the three Games were wrapped up in national hopes and aspirations of the day. For the first two Olympics, Japan was a leading power in Asia. With the third, it was no longer Asia’s top dog, surpassed economically and geopolitically by China. With its economy in a low-growth deflationary rut, Japan has suffered through its so-called “lost decades” since 1989. The just concluded Tokyo Games were meant to show the world that Japan was still dynamic, creative, innovative and prosperous.

Unfortunately, the pandemic prompted the postponement of the 2020 Olympics, the first time that any Games have had to be delayed. It was also the first Olympic Games that were held without spectators, whether local or from overseas. But by simply hosting this most logistically complex global sports festival and pulling it off without any calamity such as a major outbreak of infections among the participants, Japan scored a significant success not just for itself as a nation but also for the Olympic spirit.

Tokyo’s Olympic Games have had huge implications for China. Japan had its first IOC member in 1909, 13 years ahead of China. The first non-Western nation to be recognized as a world power, Japan served as a model and guide for China in its participation in the modern Olympic movement. As I wrote in my book, Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008, it was Japan that indirectly brought China into the Olympic fold. China’s 1895 military defeat by Japan forced the Chinese to search for a new national identity and reflect on idea of China and what it means to be Chinese.

For many centuries, the Japanese had borrowed from and been inspired by Chinese high culture, learning from China. Shortly after the Meiji restoration (started in 1868), which led to the emergence of a modernized and Westernized Japan, the nation had humiliated the Middle Kingdom. The Chinese painfully realized and accepted that its own civilization had serious challenges and that the country needed dramatic reforms of its own. As a “sick man”, China required strong medicine. Participating in international sports was one of the remedies. Since then, the Chinese had been determined to use sports and other ways of performing on the international stage to show that they are worthy competitors.

While it is too early to evaluate the 2020 Summer Games, its legacy will surely affect the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. The Chinese will be studying and learning from Tokyo’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Japanese organizers paid enormous attention to environmentally and socially friendly practices throughout the Games from the subdued opening and closing ceremonies to the use of recycled or reusable materials to make the medals and build and furnish the facilities. Beijing will have to take these efforts into account and think over what its vision for the 2022 Winter Games should be and that event should look like.

The geopolitical dimensions must be a major consideration. The world is obsessed with the rise of China and its global implications, especially for Sino-American relations. The Olympic Games can provide new perspectives to ponder that future. As I demonstrated in my recent book, Chinese and Americans: A Shared History, the US and China have common touchpoints in the Olympic movement. It was the Americans who brought the modern Olympics to China through the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). China’s first participated in the Olympic Games in Los Angeles in 1932. China’s first Olympic gold medal was won at the 1984 Los Angeles Games. Beijing even heeded the American government’s call to boycott 1980 Moscow Olympics. And the first time a sitting American president attended the opening ceremony of an Olympic Games outside the US was when George W Bush went to Beijing in 2008.

Could this shared history in sports help improve China-US relations, which have been described by some as a new Cold War rivalry? Or could the Beijing 2022 Winter Games become a source of further division and dispute, with calls for a boycott mounting?

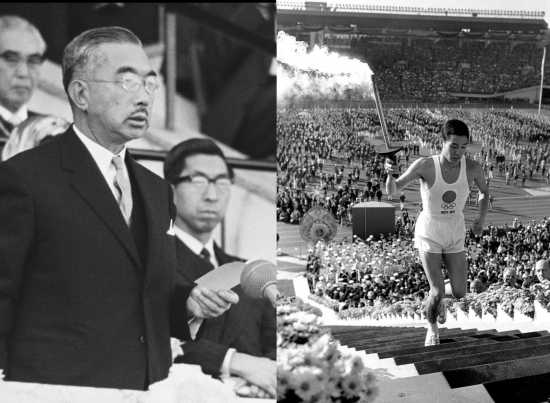

Hosting the Olympic Games is one of the most telling milestones marking a nation’s growth, development and emergence on the international stage. This was true for Japan in 1964, South Korea in 1988 and China in 2008. Bringing the Winter Games to a country may be less significant, but it is akin to icing on the celebratory cake.

Displaying sports prowess at the Games has also become a matter of national pride and stature. The US has been leading the Olympic gold medal tally since the first modern Olympiad in 1896. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) made its first appearance at an Olympics in Helsinki in1952 but refrained from participating in a Summer Games again until 1984 in Los Angeles. The PRC quickly established itself as major Olympic sporting power, coming in a constant close second in the gold medal race, even surpassing the US at Beijing. At the 2020 Games, with a haul of 39 gold medals, the US surpassed China’s count by one on the last day of competition.

Through sports, China has successfully proven that not only can it compete, it can do so at the highest level. Asian societies, especially Chinese ones, have, for centuries, been male-dominated. But in the Tokyo 2020 Games, Chinese women accounted for 69 percent of all Chinese athletes who took part, compared to 49 percent of the total for all competing members from around the world. Just over a century ago, in 1895, most Chinese women had their feet bound and were practically disabled. Today, more Olympic Gold medals have been won by Chinese women than men.

These touchstone trends are revolutionary. Can a sports revolution lead to a social revolution in China? Can the Olympics be used as a clear indicator of China’s future development towards, for example, gender equality and deeper globalization? “Revolution is not a dinner party,” Chairman Mao Zedong famously declared a long time ago. But could the Olympic movement catalyze major social and economic change in China and calm geopolitical tensions rather than inflame them? The 2020 Games arguably demonstrated how sports could overcome a global scourge. In that respect, it might truly have been the best Games ever. The coming months before Beijing hosts the Winter Olympics will offer ample opportunity to ponder the possibilities. Let the Games begin!

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.