President-elect Joe Biden has indicated what his diplomatic priorities will be in the early days of his administration: getting the US back into multilateral frameworks for climate and public health, and reconnecting with allies and partners. But, writes Alejandro Reyes of the Asia Global Institute, to change the tenor of American foreign policy and roll back the anti-globalism of Trump, the new president will have to “detrumpify” or depoliticize the bureaucracy to restore sobriety, professionalism and expertise to the conduct of foreign policy.

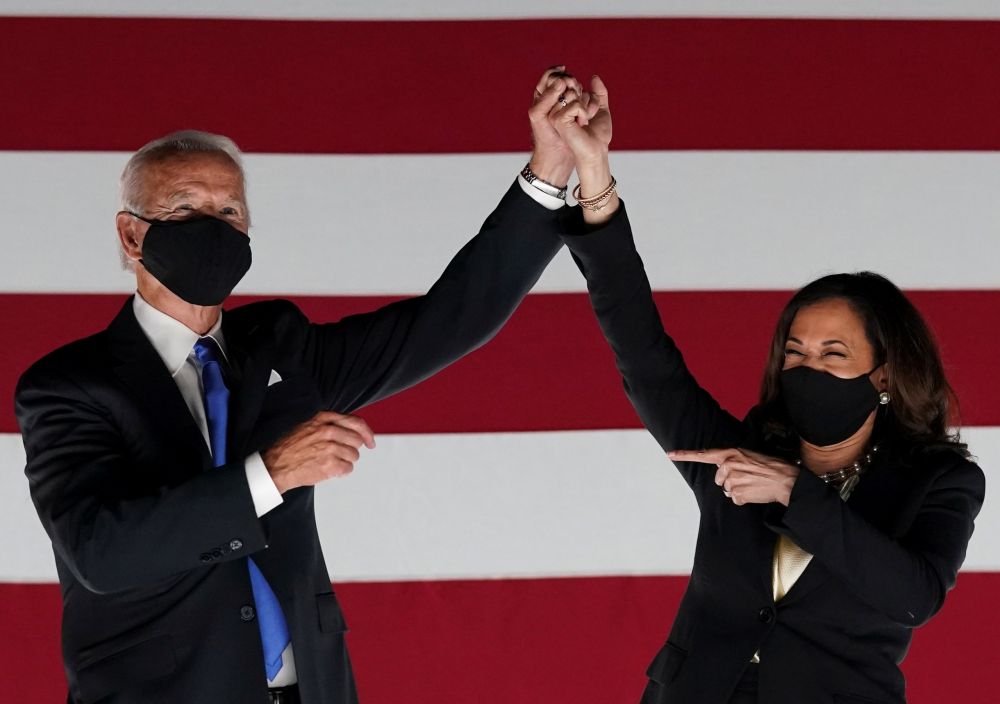

The winning ticket – Biden and running mate Kamala Harris: The new administration will re-engage with allies and partners and recommit to multilateralism (Credit: VP Brothers / Shutterstock.com)

On November 5, 2020, the United States officially withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change. The same day, Joe Biden, whom media outlets would two days later declare the winner of the presidential election, vowed that, on his first day in office on January 20 next year, he would take steps to recommit the US to the accord. During the campaign, the president-elect called global warming an “existential threat to humanity”, proposing a US$2-trillion package to stimulate the creation of green jobs and other measures to reduce US greenhouse-gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

“Welcome back America”, Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris tweeted in reaction to Biden’s pledge, noting that with the world marking the fifth anniversary of the signing of the pact, the Democratic Party ticket’s victory “symbolizes our need to act together more than ever in view of the climate emergency”. Other world leaders hailed the reversal from the science-denying policies of President Donald Trump. “With President Biden in the White House, we have the real prospect of American global leadership in tackling climate change,” British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in comments to the media.

When he returns to the White House, where he served as Barack Obama’s vice president from 2009 to 2017, Biden also promised to retract Trump’s decision to pull the US out of the World Health Organization (WHO). Trump announced the withdrawal in late May, when he accused the WHO of being in the thrall of China, which he blamed for the Covid-19 pandemic and for failing to alert the world in good time about the spreading coronavirus. Weeks later, the US notified the UN of its withdrawal, with effect on July 6, 2021.

By announcing these immediate post-inauguration moves, Biden signaled that, with Trump out of office, the US will once again be rationally engaged in multilateral organizations that it has derided and even undermined for the past four years. His vow to cancel the WHO withdrawal notice demonstrated how at the very top of Biden’s to-do list is to get control of the pandemic, which by most credible accounts the Trump administration failed to do.

Recommitting to the WHO would underscore the need for global cooperation in the battle against Covid-19, which has so far been weak. The pandemic has made even more acrimonious the already bitter relationship between the US and China, engaged as they are in a tariff war. With the coming rollout of vaccines, the world will need a more coordinated and fair approach. For now, vaccine nationalism (powerful wealthy countries spending to secure doses for their populations) and vaccine diplomacy (the less powerful scrambling for promises of allocations from the major players including China, the US, Russia and Europe) reign.

In previewing his first-day moves, Biden highlighted other priorities for his administration besides the pandemic. There is a need to shore up longstanding alliances after Trump’s erratic and cavalier approach to relationships with even the closest friends of the US such as Canada, the EU and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies. Biden will aim to regain lost ground in the fight against climate change, an issue on which in the past the US and China found a great deal of common ground – enough to catalyze the conclusion of the Paris Agreement.

Asia-Pacific countries in particular will welcome the return of the US to sober multilateralism and to taking greater care in the treatment of allies and partners. Trump’s unpredictability and mercurial style have prompted worries in the region and around the world. While some countries have supported Washington’s tougher stance towards China, more widespread have been concerns about having to choose between the two major forces in the region – the US, the guarantor of security, and a re-emerging China that has become more aggressive and vocal in asserting its power and influence, particularly in its territorial disputes with neighbors including Japan, Southeast Asian claimants to the disputed areas in the South China Sea, and India. Countries want to have autonomy to make decisions according to their own interests. If European allies join the US in countering China, this may have serious implications for Asian nations, particularly ASEAN member states.

The Trump administration’s transactional approach to diplomacy had allies and friends in Tokyo, Seoul and elsewhere wondering whether they could count on the US for strategic support as they had done in the past. President Trump’s getting-to-know-you summitry with North Korean Kim Jong-un, with whom he “fell in love”, rattled the region, especially after each photo-op meeting between the two leaders yielded little if any results in terms of progress with the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

An indication of the level of concern among Asian partners was the little-noticed passing by the US Congress of the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA), which laid out strategies for promoting American security and economic interests and values in the Indo-Pacific region. Sponsored by Senator Cory Gardner (who failed in his bid for re-election this year) and signed into law by Trump on the last day of 2018, ARIA authorized the appropriation of a mere US$1.5 billion each fiscal year from 2019 to 2023 to achieve a handful of boilerplate American goals including to “advance US foreign policy interests” and “strengthen partner nations’ democratic systems”. The true purpose of ARIA was captured in the title its authors in Congress chose – it was an anodyne articulation of Washington’s traditional approach to the Asia-Pacific meant to reassure allies and partners that they should not worry about getting undiplomatically thrown under the bus as Trump pursued his disruptive transactional strategies.

At the same time that he forced Canada and Mexico to renegotiate the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and produce the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (the USMCA, sometimes referred to as NAFTA 2.0 or the new NAFTA), Trump also threatened to withdraw the US from the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement, in effect since 2012. The US instead agreed to a renegotiation, with a new deal signed by Trump and South Korean President Moon Jae-in in New York on September 24, 2018. Critics argued that the renewed agreement was not substantially different from the previous one and contained few significant additional benefits for the US.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) has been one of the worst hit by Trump’s anti-globalist instincts. The US has blocked the appointment of new judges to the WTO’s Appellate Body, effectively paralyzing the WTO’s dispute-settlement mechanism and casting doubt on the future of the organization. With Washington out of the picture, the European Union and middle-power countries including Canada, Australia, Brazil, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Mexico and Kenya took up the pressing issue of WTO reform. The EU and Canada went so far as to develop a workaround appellate mechanism to resolve trade disputes.

In a Biden administration, the US will likely continue some of Trump’s hard-edged approach on trade, including an emphasis on buying American products, reshoring, and brining supply chains home. Washington would return to the table and contribute to the ongoing discussions aimed at reinvigorating governance over the multilateral trading system and finding ways to unblock efforts to update and make fairer the rules of the game in international trade.

While American allies and partners in the region and around the world will likely be relieved by a Biden administration’s focus on Covid-19, climate, re-engaging allies and recommitting to multilateralism, especially in trade and public health, there will continue to be grave concerns about the toxicity of US-China relations and the lack of bilateral engagement between the two powers.

During the election campaign, Biden sought to fend off Trump’s assertion that he would be weaker than the president when it comes to standing up to the Communist Party leadership in Beijing. Biden is not likely to reverse course, though he will probably make adjustments by taking a more rational, measured approach up on the rhetoric, though he will probably adjust (rationalize) the approach to China, eventually finding a way to lower if not eliminate the wide-ranging Trump tariffs, which while hurting Chinese exports to the US are paid not by China but ultimately by American consumers. Biden has suggested that he will put human rights and other bilateral irritants including the current hot issues of Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Uyghurs in Xinjiang at the forefront of his agenda with Beijing.

Trump’s clashes with China have unleashed and empowered anti-China forces inside the Beltway and beyond, with widespread talk about a new Cold War and little if any space given to those who may still want to pursue traditional constructive engagement. Since the pandemic, the rhetoric and rancor on both sides of the Pacific have overheated, with commentators now regularly referring to “a new Cold War”.

This brings to the fore perhaps Biden’s biggest priority and most pressing challenge, even as he prepares to take office: how to “detrumpify” the US government. As he has promised to “build back better” the pandemic-hit US economy, the new president will also have to build back better the professional American bureaucracy that has become more politicized than usual during the Trump years.

As much as the Trump administration has been expeditious in nominating – and getting confirmed – conservative judges to the federal bench, it has been far less efficient in filling critical policy posts. On Christmas Eve 2017, Trump nominated career diplomat Susan Thornton to be assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, a job she had held in an acting capacity since March that year. But she was never confirmed by the Senate and retired in August 2018 after she was deemed by Trump and some Republicans such as Senator Marco Rubio to be too accommodating to China. A replacement nominee was not confirmed until June 2019.

Many of those who left were replaced by young, less qualified individuals who earned their appointments because of their political connections and sentiments. All the assistant secretary of state jobs are currently occupied by acting officials or political appointees, while political appointees hold more than half the ambassador positions, nearly twice the average share in previous administrations. From the first year of the Trump administration, there were reports of the White House installing political aides in Cabinet agencies to monitor the loyalty of secretaries, acting like embedded political commissars.

An example of one such senior government appointment was Miles Taylor, who joined the Department of Homeland Security in February 2017, soon after Trump took office, eventually becoming chief of staff to the secretary. Taylor’s policy career started just 13 years ago with internships while still in university in the offices of the secretary of defense and Vice President Dick Cheney, a Republican. He was a political appointee in the administration of George W Bush. Even for a bright young man (he studied for a master’s degree at Oxford University as a Marshall Scholar) from the Midwest, his was a meteoric rise. Still only in his early 30s, Taylor had been involved in controversial homeland security policies including the "Muslim ban" and the practice of separating migrant families. (The government still cannot locate the parents of over 500 children taken away from their parents.) Taylor's conscience kicked in and he quit the administration in 2019. Prior to the election, he revealed that he was the anonymous Trump senior official who authored an opinion piece and book that claimed that he and others were working to rein in power abuses by a president he described as “impetuous, adversarial, petty and ineffective”. Taylor endorsed Biden for president.

Of course, every administration is entitled to appoint senior officials aligned with the president’s politics. At issue during the Trump years has been the quality and frequency of such appointments and how far they penetrated the bureaucracy. On November 10, Biden’s office released the names of hundreds of experts and specialists (mainly volunteering) in their camp who have joined the teams that will facilitate the transition in government agencies. The list is notable for its racial and gender diversity.

The Trump approach to staffing has had a severe impact on the level of competence, morale and the politicization of the bureaucracy. It certainly affected the way the US under Trump has conducted diplomacy around the world, with reports of disruptive tactics and hardline stances on trade and China, for example. Consider breakdowns such as the failure of leaders at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum annual meeting in Papua New Guinea in 2018 to agree on a communiqué in large part because of a behind-the-scenes clash between the US and China. The Chinese wanted traditional language countering protectionism and unilateralism, while the Americans demanded tough text decrying unfair trade practices that Washington says China pursues.

If a Biden administration is to restore normality to the conduct of foreign policy and the professionalism and expertise needed to address the most pressing diplomatic challenges, particularly the critical US-China relationship, it will have to build back the bureaucracy better and depoliticize it.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.