The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated many underlying global challenges such as the gap between rich and poor, sustainability and rising nationalism. A new dangerous kind of nationalism is on the rise amalgamating all these issues: vaccine nationalism. Sophal Ear and Japhet Quitzon of Occidental College outline the origins and dangers of vaccine nationalism and argue that developing and developed countries alike must collaborate and synchronize their public-health responses to the Covid-19 pandemic to develop meaningful viral sovereignty by building up healthcare capacity within their borders.

We're not throwing away our shot: The global scramble for a Covid-19 vaccine has spawned a new kind of nationalism (Credit: angellodeco / Shutterstock.com)

Since its emergence in early 2020, Covid-19 has upended normal life. Economies ground to a halt or slowed down abruptly and sharply, schools and businesses shut, borders closed, and millions have become unemployed. The coronavirus has spread globally, infecting some 35 million people and leaving over one million dead, as of October.

The impact on society and the global economy has already been profound, yet the pandemic is set to continue well into next year. Governments around the world have been working nonstop, enforcing appropriate social distancing and public-health measures, managing growing populations of infected people, mitigating unemployment crises, and supporting the healthcare sector.

Often, steps taken to address socioeconomic damage have turned public opinion against many governments. Citizens are upset because they perceive that their leaders are not doing enough to fight the virus or are convinced that those in charge are constraining individual freedoms. In the face of this disorder, the development of a Covid-19 vaccine has become the top priority. Life cannot return to normal without one.

Typically, pharmaceutical companies take a long time to develop a vaccine – on average, up to 10 years for research, testing and approval for general use. Clinical trials are typically undertaken in three stages: Phases one and two examine “the safety, dosage, and possible side effects and efficacy”, while phase three assesses “the efficacy of the vaccine, while monitoring for adverse reactions in hundreds to thousands of volunteers”.

Because of the severity of Covid-19, governments cannot afford to wait a decade for vaccine development. Countries and corporations have been working at breakneck speed. Over 169 Covid-19 vaccines are under development, with 26 in human trials. Among the most promising are candidates produced by AztraZeneca Oxford (UK), China National Biotec Group, Moderna (US), CanSino Biologics/Beijing Institute of Biotechnology (China), China National Pharmaceutical Group of Sinopharm, Johnson & Johnson (US), Novavax (US) and Pfizer/BioNTech/Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (US/Germany/China). While Russia’s Sputnik V shows promise, it is under intense scrutiny by researchers for questionable human trials.

The shortened vaccine development timeline presents a technical hurdle for most developed countries, despite being equipped with advanced laboratories and facilities. Consequently, international cooperation is extremely important as a unified and collaborative response to Covid-19 could produce vaccines and treatments more quickly and effectively. Efforts to drive a global effort to tackle Covid-19 have been limited, but there has been progress on the vaccine front.

In April, the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Commission and France launched COVAX, an initiative to bring together governments, global health organizations, manufacturers, scientists, civil society and philanthropic institutions and donors to provide “innovative and equitable access to Covid-19 diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines”. COVAX is meant to be a platform to support the “research, development, and manufacturing of a wide range of Covid-19 vaccine candidates, and negotiate their pricing.” All 172 participating nations, regardless of income level, will have equal access to approved vaccines – two billion safe, effective doses by the end of 2021.

Three major countries – China, Russia and the United States – had refused to join the process. But on October 9, China reversed its earlier decision. Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said that China is “taking this concrete step to ensure equitable distribution of vaccines, especially to developing countries, and hopes more capable countries will also join and support” COVAX.

Despite intense international pressure to join together and deliver results quickly, China, Russia and the US have chosen not to work together with each other. Each insists on serving their own populations first, with or without the help of the international community. Only after their own populations are served might these countries consider distributing vaccines to other nations, as they want to have complete control over the process rather than adhere to any international rules-based arrangement.

This self-interested behavior will have dire consequences for the effective global containment of Covid-19. Motivated by so-called vaccine nationalism, wealthy countries will hoard supplies of vaccines and treatments while developing nations that have been hit hard by the coronavirus would continue to struggle with limited supply and high prices.

That the US has emerged as a vaccine nationalist is of grave concern. This is an abrupt and alarming change to the world order, as it played a crucial global leadership role in disease containment during the 2009 swine flu and the 2014 Ebola outbreaks. Washington has largely shirked its traditional responsibilities during the Covid-19 pandemic and continues to cast doubt on organizations that it once supported and led, including the WHO. President Donald Trump moved first to defund the UN organization and then to withdraw from it, complaining about Chinese influence.

American vaccine nationalism was on full display early in the pandemic. In March 2020, without so much as a perfunctory nod to cooperating with an ally, the Trump administration attempted to secure for the US exclusive rights to a vaccine being developed by the German company CureVac, prompting global outcry, alarm in developing countries, and an international scramble for vaccine access rights. While wealthy, developed nations squabble among themselves, developing countries with insufficient medical research facilities and capabilities are left out in the cold, unsure of which big player to turn to for help in obtaining an effective vaccine: the WHO, China, Russia, the EU, or the US.

As developing countries lack the means to run their own pharmaceutical research, they rely on developed countries as a stable source of treatments and vaccines. With vaccine nationalism on the rise, the access of developing countries to affordable and available Covid-19 vaccines, when they become available, remains questionable. If vaccines are not readily made available and Covid-19 is not yet contained, the entire world remains in grave danger. As 2019 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Abiy Ahmed, the prime minister of Ethiopia, put it, “only a global victory can end this pandemic, not a temporary rich countries’ win.”

The issue of vaccine availability and affordability has been a thorny issue for developing countries in the past. During the avian flu outbreak in the mid-2000s, Indonesia was a hotbed for the virus. Researchers descended upon the country to extract samples for the creation of vaccines. The Indonesian government found that samples were taken out of the country without its consent and shipped off to foreign labs. In December 2006, the health minister at the time, Siti Fadilah Supari, shocked the world by declaring the H5N1 virus sovereign Indonesian property that could not be removed from the country without its explicit consent.

While developed countries were shocked and outraged at this declaration, developing countries such as neighboring Thailand and India sympathized with the minister’s message. To them, she had a fair point – how could developing countries trust developed nations to have their interests at heart and treat them fairly? Developed economies could easily take advantage of the vulnerabilities of developing countries, extract viral samples, ship them off to their R&D facilities, and sell the treatments and vaccines back at exorbitant cost. That would essentially be like holding for ransom the populations of the poorer countries.

Vaccine nationalism in the Covid-19 pandemic directly plays into the fears of developing countries that sympathized with Indonesia’s declaration of viral sovereignty 14 years ago. While collaborative programs such as COVAX may show promise, developing countries see the behavior of the US and Russia as proof of their concerns about vaccine nationalism.

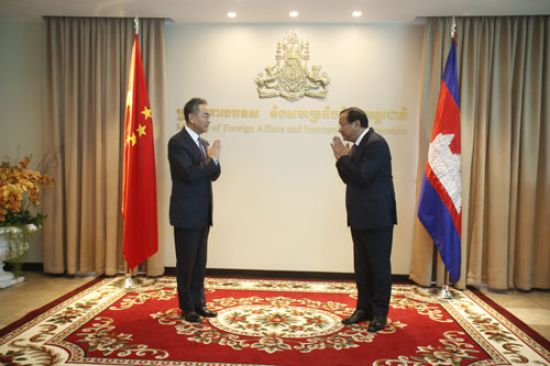

The mask diplomacy of the first months of the pandemic has given way to vaccine diplomacy. In Phnom Penh on October 12, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi promised Cambodia that it would be one of the first countries to get a Covid-19 vaccine from China. Wang recalled that Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen had visited President Xi Jinping in Beijing in February 2020, as China was in the early stages of its struggle to contain the Covid-19 outbreak. In September, Cambodia asked Russia for its vaccine. Moscow has yet to respond.

Indonesia asserted viral “sovereignty” in the sense that it cemented control and ownership within its borders over concrete things – however microscopic such as viruses. Yet claiming sovereignty over objects will do nothing to defend a country against emerging diseases that present a global threat. Moreover, merely possessing the biological material will not help a government to prepare better for handling an epidemic.

Viral sovereignty must evolve into a more meaningful policy: Countries must use the authority and power they wield within their borders to build up health capacity to join the international fight against diseases. Under meaningful viral sovereignty, all nations would be able to move toward self-sufficiency and gain the ability to perform disease surveillance and containment by themselves without worrying about having to rely on wealthier countries. With all the world’s nations empowered to contribute to the fight against disease, no one will be left behind when a pandemic hits.

The global health security chain is only as strong as its weakest link. All countries must be empowered to participate equally in a strengthened international disease-control regime. Countries with weak health systems that lack the capacity to meet basic health care needs are at the mercy of the rich developed nations that can easily buy what they may not have. If countries are able to meet fundamental health requirements, effective international cooperation would then be the most effective way to reduce vulnerabilities, pool respective strengths, and ensure that pandemics such as Covid-19 will not be as disruptive a threat in the future.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.