In its first years, China’s Belt and Road Initiative focused on publicly financed construction of land and maritime transport infrastructure corridors that linked developing-country partners to the Chinese economy. Since 2019, writes David Arase of the Asia Global Institute, Beijing’s flagship foreign economic policy initiative has entered a second phase in which attention has shifted to market integration, commercial value-chain development, and global governance with China setting standards and norms to undergird a “community of common destiny”.

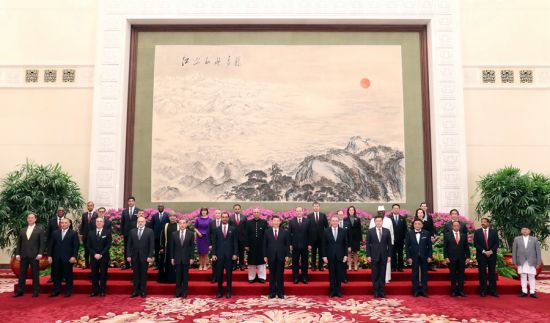

Not just about hard infrastructure anymore: Heading for a “community of common destiny” (Credit: Mike Mareen / Shutterstock.com)

China’s flagship foreign economic policy program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), began in 2013 by offering developing countries big loans to pay Chinese state-owned enterprises to build transportation, industrial, energy and mining projects linked to Beijing’s own long-term economic interests. In return, developing countries were promised growing trade and investment as China grew richer and more advanced. It appeared to be an attractive win-win proposition. Beijing quickly recruited developing countries and began building its land-and-sea BRI connectivity network encompassing Eurasia, Africa and Oceania. But this formula also accumulated risk that would later force a change of direction.

In this build-out phase, success was measured by the growth of BRI’s geographic footprint, the number of new partner country agreements, the number of new projects and loan arrangements, the penetration of markets by Chinese enterprises, the rise in trade and investment with countries in the network, and the regional and global forums where the BRI was featured as a platform for bringing together a China-led development-oriented global community to create “a community of common destiny for mankind (人类命运共同体)”.

Early rewards

The initial phase of BRI cooperation used huge official project loans to attract the partners and agreements needed to build out the land-and-sea connectivity network. By 2019, it had attracted 138 partner countries, linked China with new markets and resources around the world, and accorded Beijing the power and prestige to convene annual leaders’ forums in every region of the world except South Asia and North America (where the BRI was met with suspicion and even hostility).

In addition to partners in the continents of Asia, Europe and Africa, countries across Oceania, the South Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean signed up for BRI cooperation, giving the Chinese more secure access to all key geographies, markets and resources around the world. The BRI also gave China the status and material influence of a global power that had signed bilateral partnerships with 140 countries which gave their backing in hopes of attracting trade, investment, finance and technology. Beijing expected these nations to support China’s leadership in regional and global forums and institutions.

The BRI also had tangible effects on global trade. Whereas in 2001, 80 percent of countries traded more with the US than China, BRI helped engineer a shift under which by 2018 128 of 190 IMF members traded more with China than with the US. From 2013 to 2019, China’s trade with BRI partners totaled US$7.8 trillion. In 2019 this trade grew by 10.8 percent (compared with only 3.4 percent growth in its total trade) to reach US$1.34 trillion, or almost 30 percent of the total.

China’s annual direct investment in BRI countries remained above $100 billion from 2014 to 2019 before dropping to US$47 billion in 2020. Investment in non-BRI countries in this period was more volatile, well below the BRI figure every year except 2016-17, then falling to only US$17.1 billion in 2020. This suggests that the BRI has augmented and sustained Chinese investment in partner countries relative to the rest of the world.

Mounting costs and risks

But for all the progress the BRI had made, in 2019, it was clear that the risk-accumulating mega-project cooperation formula needed revision.

The success of the initial phase of offering huge loans to attract countries to the BRI and start projects was undeniably a great success. But by 2017, the mounting costs and risks of this strategy began to draw official concern. Beijing faced diminished foreign reserves, debt-distressed borrowers, a growing list of troubled projects, increasing domestic and overseas public scrutiny of opaque BRI lending, and new demands for domestic financing and financial de-risking. Authorities then throttled official overseas lending, which plummeted from US$76 billion in 2016 to only US$4 billion in 2019.

A recent study of 52 BRI economies by the Green Belt and Road Initiative Center – part of the International Institute for Green Finance of the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing – shows that in 2014 they held US$49 billion in official loans from China. By 2019, this figure had doubled to US$102 billion, accounting for 62 percent of what they owed to all official bilateral lenders.

These countries tended to be poor credit risks. A 2018 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report found that, of 60 BRI loan recipients, 29 were rated below investment grade and 14 had no rating at all. Only 17 were at or above the minimum investment grade rating (BBB-). And the bulk of BRI loans were pledged to the riskiest borrowers. Of the 20 top recipients of BRI loan commitments in 2019, 12 were high risk (rated six or seven on a seven-point scale). Among the top seven in this group were high risk Pakistan, Iran, Nigeria, Venezuela, and Ecuador. The other two – Russia and Indonesia – were rated at moderate risk.

There were also reputational costs and risks to consider. By 2017, the BRI “brand” was associated with commercially unviable projects and “debt trap diplomacy”. Rising awareness of environmental, social and governance, or ESG, investment compliance norms cast a spotlight on problems with sustainability and chronic issues of corruption and the misuse of loan funds. Combining these concerns with BRI’s strong element of Chinese mercantilism led to charges of neo-colonialism that reverberated through media, think-tank, and academic discourse. Beijing could ill afford this cost, which was undermining the effectiveness of its set-piece soft-power foreign policy initiative. After all, the BRI was inextricably linked to Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping’s signature concept of the “Chinese Dream” of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” and his rallying-cry rhetoric for a global “community of common destiny for mankind” under Beijing’s leadership.

The second phase

By the second Belt and Road Forum (BRF) in 2019, China had reacted to the negative risk-reward prospects of the initial cooperation phase by announcing a new “green and sustainable” era for the Belt and Road. Officials vowed to implement new programs and guidelines to incorporate ESG sustainability standards in heavy infrastructure projects.

Less noticed but perhaps more significant was a new focus on harmonizing disparate legal, policy and technical standards regimes among connected BRI countries. In his speech at the 2019 BRF, Xi emphasized that “we need to promote trade and investment liberalization and facilitation, say no to protectionism, and make economic globalization more open, inclusive, balanced and beneficial to all.” In concrete terms, this meant promoting uniform standards for free trade zones, intellectual property protection, technology transfer rules, tariff reduction, exchange-rate stabilization, trade treaty enforcement, and trade and investment dispute resolution.

“Second track” cooperation

A 2015 State Council report, “Visions and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, laid out five basic purposes and modes of BRI cooperation: policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade and investment cooperation, financial cooperation, and communications efforts to win public support. This document had already signaled that China would diversify the BRI beyond its initial steadfast focus on hard infrastructure connectivity.

To realize “high quality development”, the focus would now be on “soft” areas of cooperation. China needed to strengthen policy coordination and pursue trade and investment agreements, financial and monetary cooperation, and close political, social, and cultural engagement according to standardized institutional norms, technical specifications, and strategies across the BRI footprint, essentially integrating partner countries (which generally have been insular and protectionist) under Chinese management.

A 2018 World Bank study estimated that physical connectivity alone would boost trade among BRI countries by only 4.1 percent but if accompanied by policy reforms, the benefits would triple on average. In other words, physical connectivity improves intra-BRI trade and investment flows but not enough to justify the cost and effort. This is why the BRI needs a new wave of agreements to streamline the flow of trade, investment, money, and digital information guided by a set of institutional norms and technical standards.

Science and technology

While heavy infrastructure project cooperation would still be needed to upgrade corridor connectivity, BRI cooperation has expanded into technology – knowledge-intensive digital backbone technologies (the “digital silk road”), health-related industries (the “health silk road”), and complex 5G-based Internet-of-Things (IoT) projects such as smart cities (“innovation cooperation”). This promises to develop tomorrow’s industries for tomorrow’s markets. Under the “dual circulation” concept outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan, China will develop core technologies and commercial competitiveness in knowledge-based industries of the future to move Chinese enterprises up to the top of global value chains.

For example, applying IoT technologies into systems of governance, public service delivery, production, trade and retailing would integrate different types of value-chains and entire ecosystems of Chinese digital services, equipment, technical support, and management providers into BRI economies, putting the China atop value chains in emerging industries across the vast global BRI footprint.

Looking ahead to BRI’s third phase

Ever since the BRI’s inception in 2013, Xi had paired it with the “community of common destiny” idea of global governance which mainly targets developing countries. If countries in the network prioritize development, put aside political and cultural differences, and embrace the common goal of cooperative, comprehensive and sustainable security, then they can enjoy peaceful, harmonious development under Chinese leadership.

China believes the BRI provides the material basis for governing this community of common destiny. The task for BRI cooperation today, therefore, is to consolidate the foundation that is already in place. The heavy burden is on the second-track BRI cooperation mechanism, which requires party-state organs to build influence with political parties, parliaments, think tanks, local authorities, NGOs, industrial and commercial associations, media, and universities. Beijing must use its new hub-and-spoke network of bilateral economic and political relations to accustom 140 partner countries to China’s economic governance institutions and practices. Success will be measured by the quantity and quality of policy-coordination and trade agreements that activate economic flows across the BRI land and sea corridors. This is meant to produce a global China-led development community.

What about a phase three of BRI cooperation?

If the BRI develops into a China-centered development community of common destiny, second-track cooperation could pivot to support ongoing diplomacy work to institutionalize political and security governance overlays. At that point, BRI countries could be hard put to reject geopolitical governance under Beijing’s stewardship.

In sum, China is positioning the BRI to produce a new stage of economic integration with higher quality and more commercially driven growth managed by Chinese entities. As this plays out, expect Beijing to work hard at its dual circulation development strategy at home and its continuing efforts to match US military and diplomatic capabilities. And be prepared to hear more about a community of common destiny for mankind under Chinese leadership. The question is, how welcome around the world would such a community be?

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.