Washington’s determined pursuit of a geo-economic strategy in the Indo-Pacific could backfire, prompting rival China to work even harder to challenge US dominance while inflicting collateral damage on Southeast Asian economies, writes George Abonyi of the Sasin School of Management at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand.

Credit: William Potter / Shutterstock.com

Geo-economics – the intervention of states in economic relations to pursue strategic goals – is back. It is fundamentally reshaping the behavior of firms. But great care should be taken. Once unleashed, the effects of geo-economics are not easy to predict and control. It introduces troubling global implications and significant uncertainty, particularly in Asia.

For 40 years, approximately 1980-2019, such interventions have not played a central role in shaping world economic affairs. Disruptions such as the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami in 2011, and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 generally did not involve significant and sustained geopolitical economic interventions.

This is no longer the case. Many countries increasingly pursue political goals through economic means. Governments are constraining or displacing firms as the main decision makers in an ever-widening range of economic areas, be it medical supplies, energy or semiconductors.

Given the critical importance of the US in world affairs, its growing use of geo-economics is most significant for the future of the global economy, as well as for Asia. But this may also not be well aligned with the long-term interest of the US, particularly in the region. Primary examples of geo-economics and its risks include the weaponization of the dollar and of global supply chains. This is worrying key allies, especially in Asia, who wonder what all this means for the oft highlighted “rules-based global economic order”.

Take the US-led weaponization of the dollar by freezing Russian reserves. As the Times of India headline put it: “Question every country will ask – can US freeze my forex reserves too?”. Responses to that concern have included the recent agreement between India and Russia for trade settlement in rupees and moves by China to conduct its transactions with oil producers such as Saudi Arabia in renminbi.

Developments in Asia may be even more far reaching, particularly with respect to the role of China. An important goal for Beijing is increasing internationalization of the RMB. On a global scale, this is not likely to happen anytime soon. China is not prepared to open its capital account, necessary for a fully convertible RMB.

This could lead to growing fragmentation and instability in the global financial system. It would also expand, even if in a limited way, the regional role of the RMB and China’s influence. This is in line with the findings of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) working paper released in March 2022, “The Stealth Erosion of the Dollar Dominance: Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies”.

An even clearer signal of the central role of geo-economics for the US is Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen’s call for “friendshoring” to guide American firms’ strategies as they restructure supply chains. This weaponization of supply chains is anchored in concern with China, gaining currency with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting sanctions regime.

The basic concept sounds simple enough. Do business with like-minded friends, in particular liberal democracies with similar values. Avoid existing or potential adversaries, primarily states that are organized or that behave in what are deemed unacceptable ways. But the devil is in the details, along with a great deal of uncertainty for firms and governments, not least the US.

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated movement toward a “geo-economics of supply chains” to ensure the domestic availability of critical medical supplies. Then on October 7, 2022, the US Department of Commerce introduced export controls on advanced computing and semiconductors to China. It also signaled wider unilateral US protectionist approach towards technology trade.

The assumptions of this strategy are twofold. First, that non-US firms are unlikely to fill the technology gaps over the longer term, while China will not be able to develop an advanced semiconductor industry on its own. Second, that the US will be able to forge and maintain the needed coalition of “like-minded” partners, particularly in Asia and Europe.

These assumptions are questionable. Consider the global complexity of the semiconductor industry. It is estimated that each segment of the chip-making value chain involves firms in an average of 25 countries in direct manufacturing-related activities, as well as firms in approximately 23 countries in supporting roles. In wafer fabrication, firms in 39 countries are involved, with firms in 35 countries providing market support. A product such as an automobile, which will contain semiconductors, can cross an international border more than 70 times before reaching the end customer.

It is not clear how effective US export controls are likely to be in constraining China’s advanced computing and semiconductor development over the longer term. There is indeed a view that these controls may end up strengthening China’s chip industry, accelerating its development over the longer term.

Such trade constraints are of general concern to Asian exporters, particularly in Southeast Asia. The region’s firms, embedded in China-centered supply chains, feel particularly vulnerable by what they see as the threat implicit in “friendshoring”. In a speech in Tokyo on May 26, 2022, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warned that “such actions shut off avenues for regional growth and cooperation, deepen divisions between countries, and may precipitate the very conflicts that we all hope to avoid.”

There are also concerns with the US Inflation Reduction Act that provides extensive subsidies, much of it through tax credits, to a range of US-based industries including the automotive sector, particularly electric vehicles (EV), and renewable and green technology. Washington’s allies such as Europe and Korea have criticized this unilateral strategy, intended to de facto “reshore” supply chains. Among Southeast Asian countries, the worries may be muted but are just as palpable.

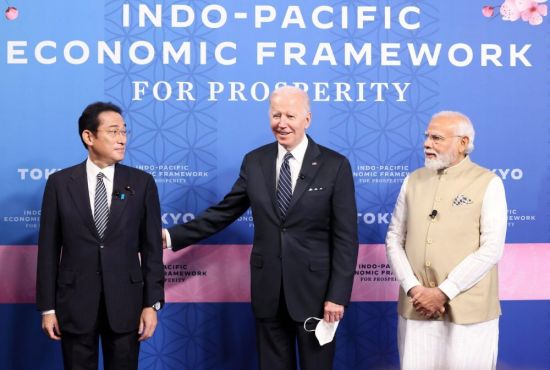

It is not clear to what extent such actions are in the long-term interest of the US. Take the example of the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) concept, a cornerstone of the American strategy for the region, largely as a response to China’s more robust foreign policy. The late Abe Shinzo coined the term in 2016 when as prime minister he sought to broaden the Asia-Pacific construct by linking the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions. This realignment placed Southeast Asia, along with India, in a central position.

The security and political focus of FOIP is clear, as reflected in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD), composed of the US, Australia, India and Japan. But its economic dimension, embodied in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), seems a more ambiguous and uncertain afterthought. It offers little that is tangible to Southeast Asian economies.

The uncertainty and risks entailed in Washington’s pursuit of its geo-economic strategy are clear and of great concern to Southeast Asian economies. The potential benefits are much less evident, particularly as compared with tangible regional initiatives such as RCEP. To elicit genuine support, the US must credibly show that the effects of sanctions and friendshoring will not hurt Southeast Asian countries, that these economies will not become collateral damage.

Moreover, initiatives such as IPEF, which is focused more on standards and rules setting rather than market access, should provide clear, credible and practical economic benefits to allies in the region. Additionally, they need to do so in a way that does not force ASEAN economies to choose sides between a China that is just across the border and a US that is over the horizon – something that most of the countries of the region are loathe to do.

The US should pursue a geo-economics strategy with great care, taking into consideration the likely impact on Asia, the global economy, and on its own long-term interests. It is a delicate business – not a matter of attempting crudely to block the adversary at every turn, but of being smart about maximizing advantages and competitiveness to stay ahead.

Further reading:

George Abonyi

Sasin School of Management, Chulalongkorn University; Fiscal Policy Research Institute (FPRI)

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.