As Japan and China prepare to mark the 50th anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic relations next year, Tokyo is confronted with its most difficult diplomatic task – balancing its strategic alliance with the United States with its economic and trade relationship with neighbor China. Into the coming year, particularly with the Beijing Winter Olympics in February, and beyond, writes Kato Yoshikazu of the Rakuten Securities Economic Research Institute and the research and consulting firm Trans-Pacific Group, Japan could demonstrate how a middle power can successfully set a path through the treacherous terrain of the great power rivalry.

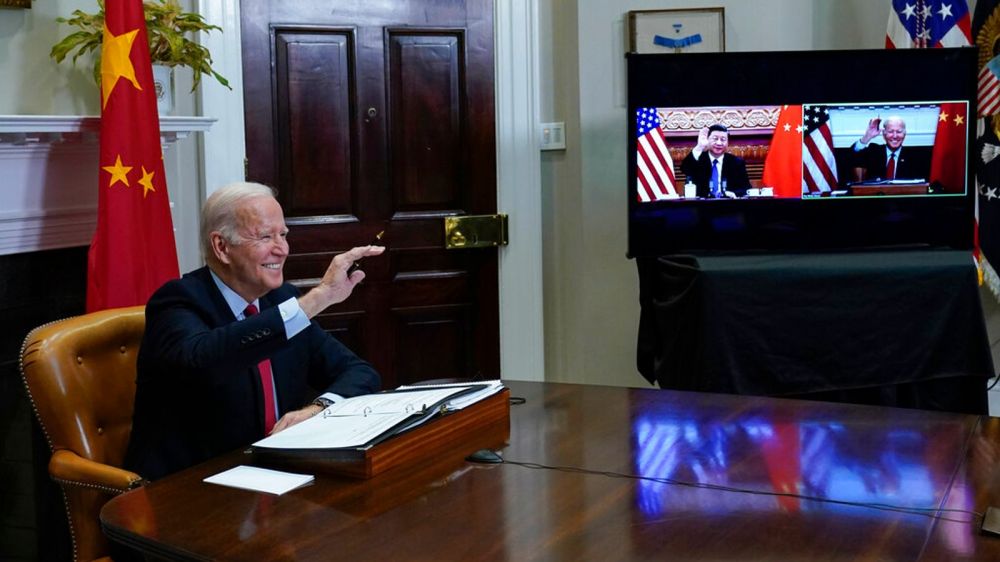

Biden and Xi go virtual, November 15, 2021: Japan is a role model for middle powers treading the treacherous terrain of the rivalry between the great powers (Credit: The White House)

A new administration took office in Japan on November 10 after a big general-election victory for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito coalition. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, who previously served in the government of Abe Shinzo as foreign minister for four years and seven months, the longest tenure of any Cabinet member in that portfolio since the end of the Second World War, revealed at a press conference how he is going to manage Japan’s complicated external relations. He expressed a desire to visit Washington as soon as possible to further enhance the Japan-US alliance and “cooperate to realize the free and open Indo-Pacific”, but added pointedly that, “in relations with China and Russia, I will claim our own stance and conduct resolute diplomacy”.

Obviously, Kishida’s top priority is to strengthen the alliance with the US in the context of the free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP). Tokyo’s relationship with Beijing should be managed within this framework and strategy. The challenge for Kishida will be tactical – how to manage Japan’s key relationships and balance the alliance with the US and its ties with China.

The Chinese seem to have high expectations. On October 4, just after Kishida won election as the president of the LDP, both Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang sent the congratulatory messages to him. Xi noted that “developing a good-neighborly friendship and cooperation between China and Japan, which are separated by only a strip of water, serves the fundamental interests of the two countries and the two peoples.” Beijing, it appeared, considers Kishida to be at least a person with whom it can talk, stabilize the bilateral relationship, and develop ties as a counterbalance to the presence and influence of the US in the Asia Pacific.

But with Hayashi in charge in at the Gaimu-shō, things may not turn out as China might hope. Nowadays, criticism of China’s internally repressive and externally assertive behavior is much wider and sharper than they were even just a few years ago. Under current circumstances, there is no market for pro-China politicians in Japan. Hayashi is extraordinarily careful to manage his own image so as not to be seen as pro-China.

Just after his appointment as foreign minister, Hayashi resigned as chairman of a supra-partisan group of lawmakers promoting relations between Japan and China. He told reporters that he made the decision to avoid "unnecessary misunderstandings" while performing his duties as foreign minister, stressing that he would be “assertive when he should be to urge responsible action” by China.

The new minister revealed the government’s game plan soon after. On a telephone call with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on November 18, Hayashi expressed serious concern about the situation in the East China Sea with the Senkaku Islands (which the Chinese call the Diaoyu Islands), as well as the issues of the South China Sea, Hong Kong and Xinjiang. He also stressed the importance of peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. These points were exactly what Wang and Xi might not have wanted to hear from the Japanese side, particularly given the sensitive times as Beijing prepares to host the Winter Olympic Games in February 2022.

Role model for balancing the relationship with the US and China?

Given these recent developments, the fundamental question for Japanese diplomacy is how Japan, as an independent nation state, defines its own power and strategy. Japan is the third largest economy in the world since China surpassed it in 2010. Japan does not have a normal military and defense capability, having only so-called Self-Defense Forces (SDF) under its pacifist post-World War II Constitution, which does not allow the nation to resolve international disputes using military force. This is the clearest and most compelling reason why the Japan-US security treaty and alliance do matter for Japan’s survival and development.

With its relatively strong economy (albeit lacking in the dynamism it used to project) and weak military and US-dependent strategic posture, as well as its unique position in international relations, Japan is sometimes categorized as a middle power – certainly one of the most important ones not just in the region but globally. As the US-China strategic rivalry continues to unfold, middle powers have become more important, especially as they might become both collateral damage in the great-power competition and key players in mitigating the negative consequences of actions by both sides. They can play a bigger role in stabilizing the international order and keeping multilateralism working.

In Japan, there has been much debate over whether the country a middle power and, if so, what this means. In his book Japan’s Middle-Power Diplomacy, Keio University professor Soeya Yoshihide argues that Japan should adopt an autonomous grand strategy as a middle power. “Middle powers”, he wrote, are “those nations that are influential economically or in terms of certain strategic aspects, but that do not aspire to rival the major nations such as the US and China in terms of hard power capabilities”. Soeya recognized that the term "middle power" has provoked negative reactions from some quarters. He defended his characterization of Japan as a middle power to suggest a strategy that is realistic and appropriate for the country’s post-Cold War future.

In early 1970s, Nakasone Yasuhiro, who served as prime minister from 1982 to 1987, described Japan as a “non-nuclear middle power” nation, stressing that he wanted to avoid referring to the country as a major power – “not small, but middle in the world”. He added: “If we put it that way, we could be secure and project to Asian countries a favorable image.”

Although the government has never either officially cast Japan as a middle power nation or stated that it conducts middle-power diplomacy, the inescapable reality is that for the country to navigate the more complicated geopolitics today, it must seek to maximize its interests as it plies a path between the two major powers. Practically speaking, the question confronting Tokyo is how to strengthen the security and strategic alliance with the US and simultaneously develop economic and diplomatic ties with China in the context of the shifting dynamics in the region. This requires Tokyo to figure out how to position itself, balance policies and hedge risks relating to this trilateral relationship.

Japan, for example, cannot put at risk its economic and trade ties with China in the way that Australia has done recently, notably in raising questions about the origins of Covid-19. Tokyo would be at pains to avoid jeopardizing its economic and diplomatic ties with China in favor of its alliance with the US. But this requires delicate balancing and finesse, especially if Japan is to refrain from taking a hostile approach towards Beijing. Japan needs both powers. The only feasible way forward is to take the stance of a middle power, often in concert with other middle powers that are confronted with the same challenge.

The case of the Beijing Winter Olympic Games could be typical. US President Joe Biden recently said that Washington is considering a diplomatic boycott of the event. If the US rallies allies and partnerships to take such action, this could lead to a major blow for Beijing, likely to stir up resentment among Chinese people and a negative reaction by the government. Responding to Biden’s statement, Kishida was careful not to support the idea of a boycott so readily. “Japan will consider its stance on the Beijing Winter Olympics on its own terms,” he said.

Another important issue that will test Japan’s middle-power diplomatic skills is the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the high-level free-trade agreement initiated by the US (as the TPP) that Japan led to a successful conclusion in 2018 in concert with other middle powers after Washington withdrew from the pact in January 2017. Since the CPTPP came into force nearly three years ago (so far, eight of the 11 members have ratified and deposited their accession documents), applicants to join have emerged – the UK and almost simultaneously, China and Taiwan, which is part of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum as Chinese Taipei.

How CPTPP signatories deal with the applications will certainly be a major diplomatic challenge. In 2022, Singapore will succeed Japan as chair of the CPTPP commission. Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong is reported to have expressed support for Beijing’s bid to join in a call with Xi. Lee has been a major voice calling on the US and China not let their “corrosive” relationship force countries caught in the middle to have to make a choice.

“There are three concepts which describe this region,” a senior Japanese government official explained. “‘Asia Pacific’ – simply a geographical concept, “Indo-Pacific” – a politically charged anti-China concept, and ‘Trans-Pacific – a strategic rules- and values-based concept. We should pick the last one and not call ourselves an Indo-Pacific nation like the United States; we are different.”

As the official pointed out, the US and Japan’s stances on the Indo-Pacific are slightly but significantly different. Japan has said that it fully shares the FOIP vision with the US but Tokyo has never stated that Japan is an Indo-Pacific nation. It has not established a specific division in the government for the Indo-Pacific issues. Contrast this with Biden’s appointment of Kurt Campbell to be his National Security Council Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific. In other words, Japan is independent when it comes to the implementation of the FOIP idea. This is the principle guiding Kishida and Hayashi.

With regard to the CPTPP, what Japan should do with other members, particularly fellow middle powers close to the US such as Australia and Canada, is to deal fairly with China and Taiwan based on the rules and principles of the partnership. They cannot make any decisions or compromises driven by geopolitics. And more importantly, Japan should actively and patiently convince the US to come back into the fold. China’s entry in the absence of the US would not suit neither Japan’s national interest nor the rules and values-based regional architecture. Japan has to seek ways to facilitate US-China co-existence within this order. Depending on its economic might and diplomatic prowess is the only feasible strategy for Japan. It is what a middle power in the Trans-Pacific region needs to do to survive.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.