The changing way that the US wields power in the world and its tougher approach to China, playing out long before the presidential election, are forcing Asian countries to rethink their relationships with Washington and Beijing, writes Vasuki Shastry of Chatham House.

Credit: Poring Studio / Shutterstock.com

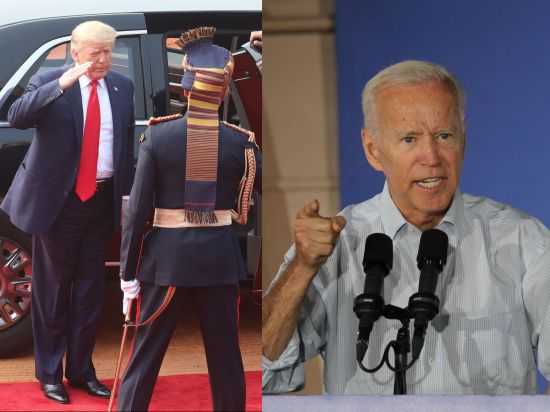

If there is one macro message for Asia from the photo-finish outcome of the US presidential race, it is the following: Populism has prevailed and the era of a narrow elite determining US foreign policy, without the input of a less-interested electorate, has surely come to an end. Of course incoming presidents, including incumbents, are voted in based on grandiose promises made on the campaign trail to restore America’s economic standing at home, to resist the temptation to launch foreign military adventures, and to focus policy attention on forgotten voters (rural, white Americans, people of color). The key lesson from the turbulent 2020 election is that Donald Trump’s vision of America First has been embraced across the political spectrum.

For Asia, regardless of who ends up victorious (as of publishing, Trump’s Democratic Party opponent Joseph Biden appeared to be in a better position to win), this means bracing for policy turbulence, with fraught US-China relations at the epicenter of how America will approach the region in business, trade, investment, standard setting, and regional security. To paraphrase the immortal words of the Italian writer Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, if Asia wants things to stay as they are, things will have to change.

An early hint of what this change looks like came from the results themselves. While Biden looks set to secure a popular-vote majority of over 3 million, there is no denying that American voters across the country have signaled that they like Trump’s muscular and sometimes erratic approach in dealing with the rest of the world. Indeed, Biden and Trump each claimed to be the candidate who would be tougher on China. With a shrinking base of electoral support for the rules-based international order, which America itself created, a President Biden will have to tread cautiously in seeking to preserve and build on the pre-2017 world. Any talk of turning the clock back to that more hopeful era is fanciful.

American voters also do not seem to mind that their president in effect bullies friends and allies alike. This hectoring was on full display in Asia just before the election when Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, one of Trump’s more robust supporters in the Cabinet, conducted a whistle-stop “anti-China” tour across South and Southeast Asia. This was preceded earlier in the month by a visit by Pompeo (reckoned to be considering a run for the presidency in 2024) to Tokyo for a meeting of foreign ministers of the so-called Quad nations – America, Australia, Japan and India.

For some countries in the region, the bombastic Pompeo’s presence was too little and too late. It had the signature imprint of a farewell tour by a senior American official. The blunt message he conveyed about countering China’s growing influence was not backed by policy and financial muscle. The fact that many Asian leaders, notably the presidents of Sri Lanka and Indonesia, attempted to distance themselves from Pompeo’s fiery anti-Beijing rhetoric demonstrates the region’s unease on the central issue of taking sides in the continuing US-China Cold War.

There is, however, an alternative, more compelling view that the tone and rhetoric on display by Pompeo during his swings across Asia indicate precisely how America is going to interact with the region in coming years, regardless of who the President is likely to be. The pivot, much heralded in Asia in 2009 when the administration of Barack Obama declared that it would be shifting strategic attention and security assets, is finally taking place, although in scale and impact this may not be what the region had in mind.

A new American approach will include these elements:

A more muscular American presence in Asia will be built on overwhelming public support at home to counter China. This is a game-changer because Americans across the political spectrum support the administration taking a more hawkish stance toward China. It is hard to think of a precedent in recent US-Asia relations where the American public has weighed in and indicated its preferred policy approach. It will therefore be very hard for a president to ignore one of the central messages of the election. The country is hopelessly divided on domestic issues and will not be bothered with what is happening in the rest of the world.

Support for free trade and 2010-era regional trade agreements are dead in the water. Any expectation that a Biden administration would try to rewind the clock back to the bygone era of free-trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), from which Trump withdrew the US soon after taking office in 2017, is wishful thinking. This does not mean that Washington will turn its back on free trade but future agreements will have to come with plenty of safeguards for American workers, measures for the protection of intellectual property rights, and tough environmental and labor standards (even more stringent than were included in the TPP) that previous administrations had been loath to pursue. In Asia, most closely watched will be the battle over ASEAN, as pro-China members in the regional grouping (Cambodia, Laos and possibly others) have become more vocal, and negotiations are winding down on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which Beijing has spearheaded. A unilateral America may well force ASEAN to make strategic choices on how RCEP is implemented and other trade matters including supply chains, especially relating to technology and other strategically important goods. This could threaten to undermine Southeast Asia’s most spectacular achievement – its burgeoning intra-regional trade and integration with the major economies of North Asia including China. Consider how the Trump administration forced the insertion of a clause into the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA, often referred to as NAFTA 2.0) that requires signatories to advise the other parties of plans to conclude any free-trade deal with a non-market economy and to submit agreement texts for their review.

Decoupling is for real but will be messy and expensive. The US and China will have to come to terms with the reality that, in their new roles as cold warriors, it is unsustainable for them to maintain the world’s deepest economic relationship. A primary US business concern in the next few weeks will be to ensure they have a seat at the table when the new administration determines the future contours of the economic and trade relationship with China. American business will urge caution and pragmatism, eager to protect gains so far, but the political and public winds favor a reordering of the relationship. After all, on the stump, Biden embraced a “buy American” policy not dissimilar from Trump’s. This will mean the reconfiguration of regional supply chains, the inevitable delineation of the region into distinct Chinese and American spheres of influence. The best that the business community can hope for is that this realignment process is protracted, and every attempt is made not to disrupt existing economic value chains.

Human rights will make a decisive comeback, a major shock for the region. America’s ambiguous positioning in recent years on decisive human rights issues such as the protests in Hong Kong and Thailand, and the detention of millions of Uyghurs in deradicalization camps provided the region with a respite. During his tour, Secretary Pompeo’s pronouncements, certainly on Thailand, signaled a shift in positioning. A hectoring America will once again preach the virtues of democracy, free speech, human rights and gender equality. A new administration will tie progress on these issues with access to vital US markets. Asia’s anxious youth, whose prospects have been wracked by the pandemic and even before that by a more challenging employment picture, will be emboldened by a much more robust American approach to human rights enough to challenge the political status quo on their home turf.

On all these fronts, what with the changing and challenging leadership dynamics in China and the US, there is no doubt that Asia has decisively entered a more uncertain, less stable era. Asian countries have a choice in this burgeoning Cold War between an incumbent and rising superpower. Being a passive recipient of a benign global order has its limits. The region needs to stand its ground and emphatically advocate for regional stability. History’s lesson is that great powers often stumble into conflict – and it is time for Asia’s middle powers to play an active role in shaping the region’s future security and economic architecture.

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.