Covid-19 has halted a slow rapprochement in Sino-Japanese relations, writes David Arase, visiting professor at the Asia Global Institute at The University of Hong Kong. The pandemic, he adds, has also revealed new insights into what the Indo-Pacific may expect from China and the US as the two compete for regional leadership. The diminished prestige of both China and the US after Covid-19 will prompt Japan to step up its engagement with like-minded middle and smaller powers to reinforce strategic stability and the existing rules-based order.

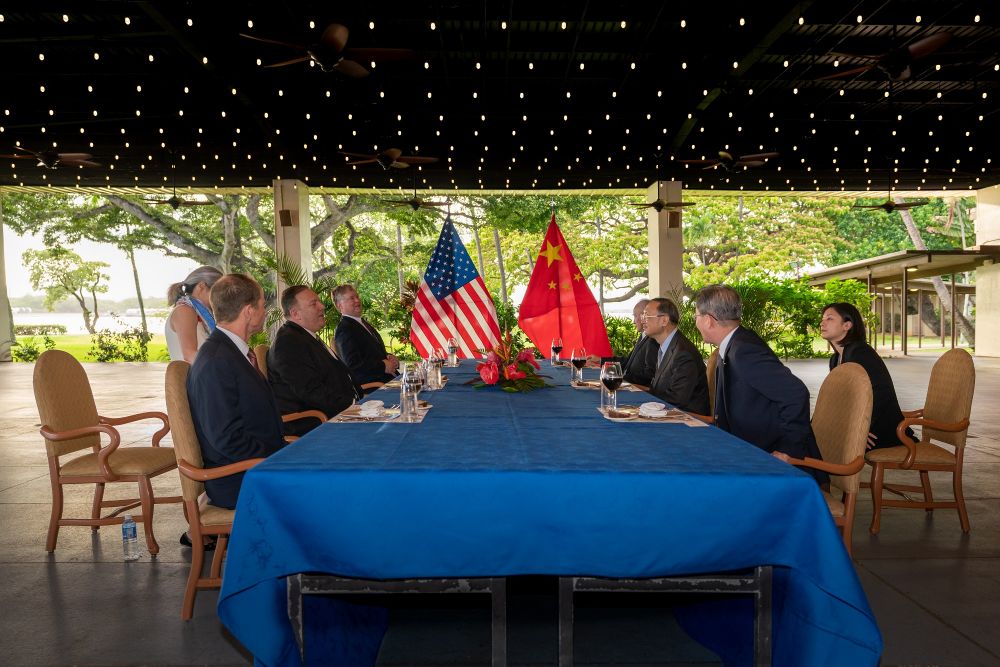

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo hosts Chinese State Councillor Yang Jiechi at a working dinner, Honolulu, Hawaii, June 16: While the rivals bicker, Tokyo worries about a leadership void in the Indo-Pacific (Credit: Ron Przysucha/US Department of State)

After the US launched its first trade measure against China in March 2018, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang traveled to Tokyo that May to backstop China’s trade relations with Japan and South Korea. His goals were to warn Japan against siding with the US against China, revive dormant three-way talks on a Northeast Asian free-trade agreement, and enlist Japan’s support for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Li was received cordially by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who saw an opportunity to calm Japan’s territorial conflict with China, maintain access to the growing Chinese economy, and promote regional stability and prosperity in cooperation with China, while remaining within the framework of the US-Japan alliance. Li invited Abe to visit Beijing to discuss improved bilateral relations.

Abe traveled to the Chinese capital in October 2018 and pledged a “new era” of “collaboration not competition” in bilateral ties that would be sealed by agreements to be signed during a return visit by Chinese leader Xi Jinping scheduled for April 2020. But the visit had to be put off because of the Covid-19 epidemic. Since then, however, regional developments catalyzed by Covid-19 have done much more than delay this Sino-Japanese rapprochement. It seems to have derailed it entirely.

Why did Abe pursue rapprochement?

Because it is neighbor to a revisionist China that has little regard for international norms and poses risks to its sovereignty, security, economy and political standing in the world, Japan has relied on the US to defend it. At the same time, Japan has engaged economically with China to enhance Japan’s prosperity and future economic prospects. But the resulting Sino-Japanese relationship is narrowly based on China’s diminishing need for Japanese capital, goods and technology.

Meanwhile, China’s political and strategic animosity directed against Japan has intensified over time, as demonstrated by increasing military maneuvering in and around the Japanese islands. Worst of all, Japan’s ties with China are hostage to continuing instability in US-China relations, the outlook for which is decidedly negative. Add to this the longstanding disputes over wartime atrocities and Japan’s treatment of their history. All this means that Tokyo’s bilateral relationship with Beijing has hardly been stable or smooth.

Abe would have liked to remedy this situation by adding new dimensions to the bilateral relationship. One would have been a strategic economic partnership to cooperatively develop the Indo-Pacific region. Another would have been a military-strategic relationship to preserve stability, starting with bilateral crisis management. The ultimate goal: a normal political relationship unhindered by animosities and grounded in mutual respect, mutual benefit, and a meaningful regional partnership.

Covid-19 intervenes

The Covid-19 crisis revealed much about each country’s fundamental strengths, weaknesses and motivations. What Japan is learning about its regional neighbor most likely will not only derail its rapprochement with China and force it into closer strategic alignment with the US, it will also probably invigorate independent Japanese efforts to reinforce its own security and strengthen open rules-based regional order. With the US, Japan has already been championing the concept of a “free and open Indo-Pacific”.

While the rest of the world was preoccupied with managing the pandemic, China moved opportunistically in the South China Sea, East China Sea, Taiwan Strait, along the Sino-Indian border, and in Hong Kong – as if to steal a march on ongoing sovereignty disputes while the rest of the world was weakened and distracted by the pandemic.

In the East China Sea, two Chinese coast guard ships entered Japanese-administered territorial waters of the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands on May 10 and ordered a Japanese fishing vessel to leave the area. In mid-May, China began large-scale naval military exercises in the Yellow Sea that are scheduled to move southward and last until August to include a simulated takeover of the Taiwan-administered Pratas Islands. In the South China Sea in April and May, China sank a Vietnamese fishing vessel, operated a survey vessel inside Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), declared the establishment of Paracel and Spratly islands administrative districts, and named some 80 contested land features.

Along the Sino-Indian border, Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed in Ladakh on May 5 and 9, and on June 15, violent fighting near the Galwan River led to the deaths of 20 Indian troops, with casualties on the Chinese side undisclosed.

Then on May 22, China announced its intention to circumvent the Hong Kong legislature and impose a national security law in Hong Kong that would criminalize political protest, and dissent. It would also allow Chinese domestic security agencies to operate in Hong Kong. The law went into effect on June 30.

In sum, during Covid-19, China put on a disturbing display of how, when given a free hand, it can behave toward those who resist its demands.

Meanwhile, the US administration’s management of the Covid-19 epidemic and its harsh rhetoric directed against China and the World Health Organization (WHO) have reinforced Japan’s negative perception of US President Donald Trump as an unpredictable and intemperate president who is difficult to trust. Covid-19 also interfered with US naval readiness in the Indo-Pacific when the US aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt was forced to cut short its Western Pacific patrol and dock in Guam in March because of coronavirus cases on board. A large portion of the crew of the US destroyer Kidd also tested positive for the virus while docked in San Diego. These developments had an unsettling effect on Japan, which relies so heavily on a strong US military presence in the region.

At the same time, Covid-19 exacerbated existing economic, political and security tensions between China and the US, which have been locked in a trade war. Both sides cast blame on the other for originating and spreading the virus. Further irking Washington were China’s coercive efforts to change the regional status quo, exploit the crisis through its face mask diplomacy, and impose trade sanctions on Australia because Canberra called for an independent inquiry into the origins of Covid-19. With relations with China emerging as a major issue in the US presidential election in November, many in the US in both political parties have become convinced that differences with Beijing are irreconcilable and that Washington needs to confront China even more. This has forced Japan into a difficult situation – its actions risk displeasing one or the other of the strategic competitors in the region.

Leadership void in the Indo-Pacific

During the pandemic, several countries in the Indo-Pacific have experienced lower infection rates, fewer days in lockdown, and milder economic effects. Because the region is less dependent on commodity exports and is more integrated into global value chains, prospects for economic recovery are good. Countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand struck a more successful balance between lockdown measures and maintenance of normal economic and social life. Japan’s interests closely align with all of these capably governed countries.

This clear Japanese alignment with the US against China’s actions in Hong Kong likely marks the end of Abe’s search for a “new era” in Sino-Japanese relations. Abe’s initiative never had much hope of prospering. China is not about to abandon its great national rejuvenation agenda to conform with “Western” legal norms, nor is it going to concede so much to Abe without demanding a steep price in return. The most likely demands? An end to US-Japan partnership, full political and economic support for China’s continuing rise, and subordination to a China-centered “community of common destiny”.

Japan recalibrates

China’s failure both to contain Covid-19 at the initial stages of the outbreak and then to cooperate effectively with other countries once the virus had spread beyond its borders revealed previously underappreciated security and economic risks associated with supply chains that make critically needed goods and rely so heavily on China. To counter these risks, Japan included in its Covid-19 emergency budget a special allocation of US$2.2 billion to subsidize the selective reshoring and dispersal to other Indo-Pacific economies of Japanese supply chains in China. This move will not have a dramatic effect on Japan’s economic ties with China, but it does reflect a reassessment of China’s stability and reliability.

Sharpened geopolitical tensions create a higher risk with respect to renminbi (RMB) devaluation, stricter RMB currency control, dollar liquidity, and China’s export and GDP growth prospects. High unemployment and lower growth triggered by Covid-19, as well as a mounting load of debt, raise the threat of asset deflation. These risks are intimately connected to social stability in China. Beijing is known to channel social discontent toward foreign targets. No country may be more convenient for this purpose than Japan. The Japanese would, therefore, be prudent to limit their dependence on the Chinese economy and be more strategic in diversifying their trade and investment relations.

Meanwhile, US failure to show leadership and inspire confidence in this crisis will cause Japan to become more independent and forward thinking. With the greater uncertainty, the US-Japan alliance remains critically important, but Japan needs enhanced defensive capabilities and more robust regional relationships even as it is forced into closer alignment with the US. Japan will continue to step up its international engagements, particularly with Southeast Asia and India, while partnering with the US to implement its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. Japan has little choice but to take more initiative to support the rules-based order as it did when it salvaged the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) after the US pulled out of the trade agreement.

As it surveys the region today Tokyo will have taken notice of a number of developments driven in large part by China’s bullying and disappointing US leadership. Australia and India signed a landmark agreement to permit mutual military logistics support. The Philippines suspended its move to end its Visiting Forces Agreement with the US. (With its own agreement for hosting American troops set to expire in March 2021, Japan is itself moving forward with negotiations with the US on a new deal.) Indonesia notified the UN that China’s South China Sea territorial claim endangers Indonesia’s EEZ rights. South Korea accepted Trump’s invitation to the expanded G-7 meeting. And the EU – an important external stakeholder – has postponed its long-awaited summit meeting with Xi planned for September. Perhaps it is time for Japan, together with these like-minded countries, to take greater responsibility for regional governance.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.