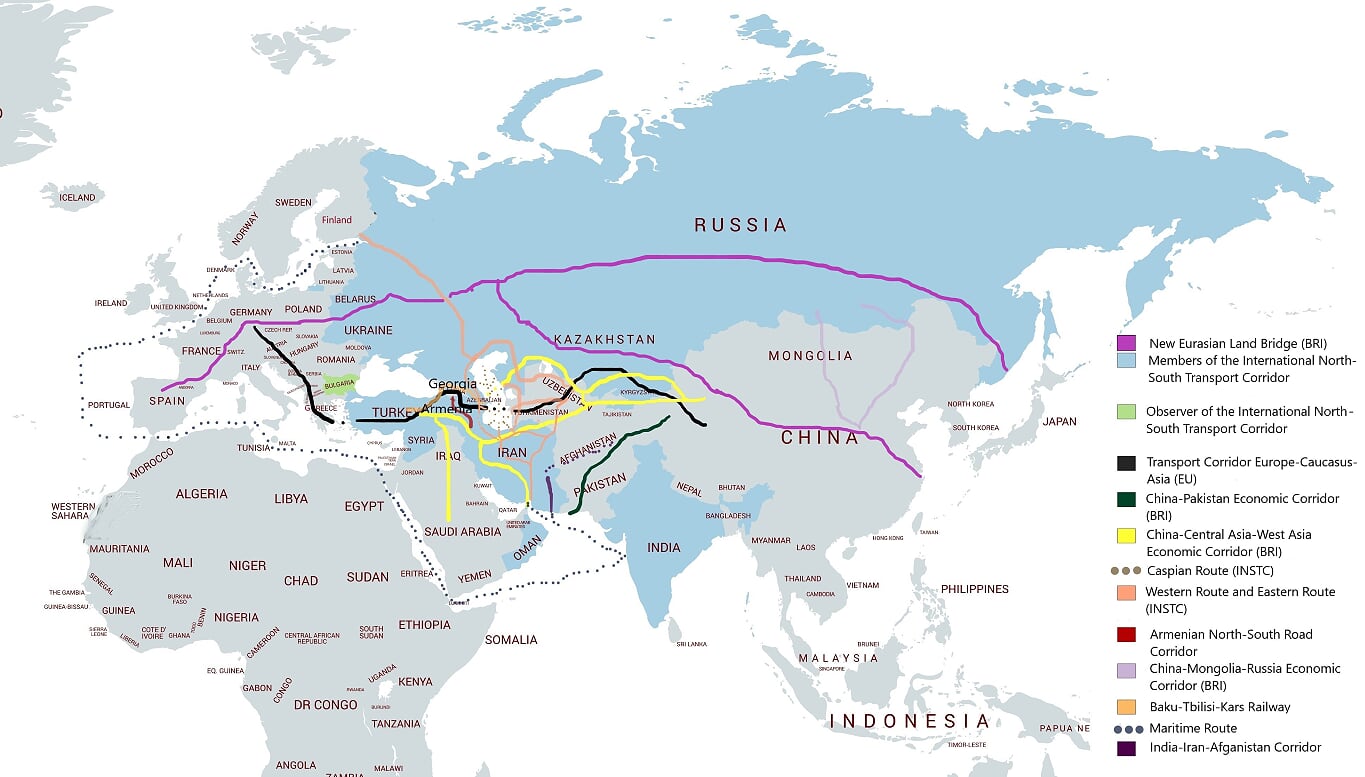

In an age of interconnectivity, China’s Belt and Road Initiative stands out as a political and financial behemoth, a network spanning the world with road, rail and sea links. But, writes AsiaGlobal Fellow Mher Sahakyan, founder and director of the China-Eurasia Council for Political and Strategic Research, the lesser-known International North-South Transport Corridor, founded 20 years ago and led by Russia and India, could emerge as a geopolitical rival to the BRI if it can overcome financing issues and ongoing conflict among the signatories.

Iranian train rolls into Gyzyletrek, Turkmenistan, to inaugurate the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran railway link, 2014: The eastern route is one of the most successful of the links between Russia and India in the INSTC network (Credit: Moein Motlagh/Fars News Agency)

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, ending the Cold War, India not only lost its most reliable supplier of weapons, it also lost its most important partner in countering China because of the subsequent normalization of relations between Beijing and Moscow. But as Russia, the USSR’s successor state, descended into economic chaos in the 1990s, India continued to import Russian weapons and looked to re-establish its special relations with Moscow. After Vladimir Putin came to power on the last day of 1999, Moscow achieved a measure of political and economic stability and began to look for strategic partnerships beyond the now-independent former Soviet republics.

One of the first countries with which Russia tried to strengthen its relations was India. These two non-Western countries implemented steps for restore their strategic partnership and recapture their positions as great powers. Among the earliest and most ambitious projects that they initiated was the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC, see box below). Russia and India involved Iran as well, due to its location at an especially important crossroads, establishing the INSTC secretariat in Tehran. Later, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Oman, Tajikistan, Syria, Ukraine and Turkey signed up as member nations, while Bulgaria obtained observer status.

Russia and India thus created the foundation for a road-and-sea corridor linking their countries with each other through Iran, Central Asia and the South Caucasus. In turn, Iran became a bridge between Russia and India. Under the INSTC plan, Novorossiysk on the Black Sea could be linked to Finland, and Berlin with Ekaterinburg, east of the Urals, while the transport infrastructure of the Volga and Don rivers and the Caspian seaports could become interconnected. Moreover, the INSTC would directly link St Petersburg with Mumbai.

The INSTC and Russian interests

Moscow envisioned that the INSTC would operate as a multimodal route for transporting passengers and goods between India and Russia through Iran and the Gulf states. In proposing the INSTC, Russia aimed to create an alternative to the Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA) of the European Union (EU), which was also launched after the collapse of Soviet Union to connect Europe with the South Caucasus and Asia without passing through Russian territory.

Russian decision makers also thought that China’s growing export-driven economy could utilize a transportation corridor such as the INSTC, but eventually Beijing had its own geopolitical initiatives, building a huge trade infrastructure network that developed into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which includes the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), which consists of six economic corridors through the Eurasian mainland, obviating the need for the INSTC.

For now, Russia and the other members of the INSTC hope that as a result of the economic growth of India, the corridor will be used more. Before the pandemic, the World Economic Forum forecast that India’s economy would grow 7.5 percent a year over the next decade. In addition, given worsening Sino-Indian relations, New Delhi might be more interested in developing the INSTC as a counterweight to the BRI’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

The INSTC and Indian interests

India sees the INSTC as an import-export route to Russia, Europe and Central Asia that bypasses archrival Pakistan and strengthens its cooperation with Russia and other members of the project. Mumbai would thus be connected to Iran’s railway and highway network through the port of Bandar Abbas, one of the main gateways to the Gulf region. India agreed to invest up to US$635 million to develop the Iranian deep-sea port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman and only 300 kilometers from Gwadar, the hub for the CPEC in Pakistan.

New Delhi, meanwhile, convinced the US not to impose any sanctions on Indian investment in Chabahar, despite Washington’s economic isolation of Iran. Chabahar would be used by India as a staging point for its development initiatives in landlocked Afghanistan’s development and for strengthening India’s positions against China and Pakistan. New Delhi is also interested in securing the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) or Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani was on hand in the city of Herat to celebrate the arrival of the TAPI in Afghanistan in February 2018. The development of Chabahar and an India-Iran-Afghanistan corridor represents a unique case of Iran and US interests converging, as both nations are intent on improving the economic and political security of Afghanistan.

In sum, India is trying to use the INSTC not only to create an economic corridor and develop relations with Russia and Europe but also to reach out to other regions. India is very interested in the energy resources and vast market of Central Asia (with a total population of about 74 million). Cooperation with the Gulf states is also important for New Delhi, as in addition to oil and gas resources, they provide employment opportunities for an estimated 8.5 million Indians. Finally, India is a signatory to the Agreement on the Establishment of an International Transport and Transit Corridor, known as the Ashgabat Agreement, which is a platform for India to discuss discreetly transportation issues with Pakistan.

Obstacles to the INSTC

While the INSTC brings advantages over traditional goods routes through lower-cost and shorter distances, development of the required infrastructure has been slow, especially when compared with the BRI. There is no driving political of financial force behind the INSTC in the way that China has relentlessly pushed forward the BRI. Beijing created dedicated financial institutions and instruments (the Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) to keep up the tempo of development. INSTC projects are mostly financed through loans provided by the ADB, the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB), and other institutions, or by INSTC members investing directly in their own or their neighbors’ projects. If China’s initiative is being developed in a planned and organized way, the INSTC is proceeding in an ad-hoc manner without any long-term strategy.

Moreover, there are several ongoing conflicts among INSTC member states. Because of the Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Turkey-Armenia-Azerbaijan and Armenia-Nakhijevan (Azerbaijan)-Iran railways are not operating. The connection between Russia and Georgia through Abkhazia is also not operating because of the conflict between Georgia on one side and Abkhazia and Russia on the other side. The Russo-Ukrainian conflict makes transportation through Eastern Ukraine extremely difficult. The chaotic situation in Syria and the unstable situation on the Turkish-Syrian border are making it impossible to develop the INSTC in that direction. In addition, Iran's economy and financial sector are under the heavy sanctions imposed by the US.

These political and strategic conditions have created many problems for the INSTC, as many states and companies are finding other routes for transporting their goods. But they are also creating new opportunities. Iran and China have been brought closer together due to the US sanctions, A draft Iran-China partnership was approved by Tehran in June. India, meanwhile, has been pivoting toward the US since its armed border confrontation with China that same month. This could herald changes in Indo-Iranian relations, though it might create an uneasy situation in which Tehran might have to make a strategic choice between India’s INSTC and China’s BRI.

Russia also faces Western sanctions due to its military and political involvement in Ukraine, making it harder for Moscow to make major investments in infrastructure projects in other INSTC member states. Russia is also participating in China’s BRI through the New Eurasian Land Bridge and the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor. Moscow, however, is not about to play a secondary role to Beijing. For this reason, Russia values the INSTC and Russo-Indian cooperation, as Russia sees India as a partner for balancing power with the Asian superpower, China. In this context, the INSTC could become an important economic and strategic tool connecting Russia with the Gulf region and Indian Ocean.

The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC): Connecting Russia to the Gulf and India

The traditional maritime route from St Petersburg in Russia to the Gulf region and India runs through the Baltic and North Seas and the English Channel, past France and down to and around the Iberian Peninsula, along the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal, and then to Bandar Abbas in Iran or to Mumbai. A container ship takes between 25-28 days to reach Bandar Abbas, while the voyage to Mumbai requires about 30 days. The INSTC cuts the distance and time by at least half, significantly reducing transportation costs.

Credit: Mher D Sahakyan

The INSTC has four main routes:

Further reading:

Mher Sahakyan

2022 AsiaGlobal Fellow, Asia Global Institute, The University of Hong Kong, and the China-Eurasia Council for Political and Strategic Research

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.