The second wave of coronavirus devastating India would have crippled most governments. But Narendra Modi is no ordinary leader, writes Vasuki Shastry of Chatham House. The prime minister’s personal popularity ratings have consistently been substantially higher than that of the ruling party, which suggests he might well ride out this storm with ease. While he is helped by a grievously weak opposition, he has failed in channeling public anger and articulating an alternative policy path.

Prime Minister Modi gets immunized: But the vaccine cannot inoculate him from the criticisms of his performance during the pandemic (Credit: YashSD / Shutterstock.com)

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, is the master of pithy slogans. During the 2014 elections, which vaulted him and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) into power, Modi pledged that his administration would offer “minimum government, maximum governance”. In good measure, he also promised Indians that good days (acche din in Hindi) were just around the corner.

But as India reels from the deadly second wave of the pandemic, possibly its worst crisis since independence in 1947, these slogans are beginning to haunt the image-conscious leader. As the pandemic overwhelms the country’s once-admired administrative machinery, ordinary Indians are facing what appears more like “minimum government, minimum governance” as caseloads and the death toll rise exponentially each day. Social media, meanwhile, has effectively replaced the health ministry in delivering urgent care and in coordinating the public response.

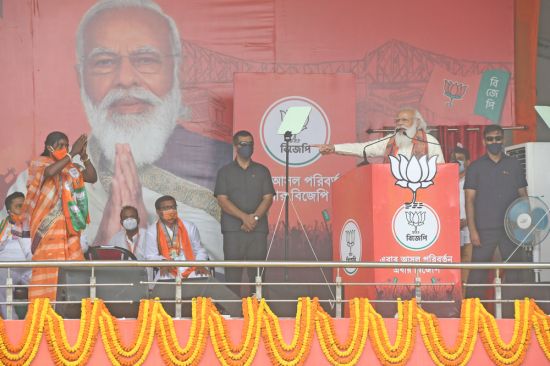

Modi, whose time for much of the past three months was consumed with electioneering in the eastern state of West Bengal (where the BJP was routed), has all but disappeared from public view. In the eyes of his critics, he and his government’s malign incompetence have cost lives and exacerbated the public-health debacle. The prime minister’s propagandists have offered a weak defense of the government’s mishandling of the crisis. But looking closer at Modi’s leadership style offers revealing clues as to why it may be ill suited to deal with a national emergency.

To be sure, Modi does have a cabinet of ministers, some good, many inexperienced, whose primary task appears is to be implementing the wishes of the PMO. The story is perhaps apocryphal, but in the early days of Modi’s tenure in 2014, the PMO is said to have called a minister on his way to the airport to return home and change his clothing. The minister was apparently wearing jeans, which the PMO regarded as inappropriate attire for a member of the cabinet.

This lack of autonomy – and the fear it instills – can perhaps explain why the government’s National Scientific Task Force for Covid-19, the umbrella committee established to manage the pandemic, did not meet in February or March as the second wave accelerated and timely intervention could have saved the day. Modi’s preoccupation with winning the elections in West Bengal, where he ceaselessly campaigned during much of the same period with nothing to show for his efforts, will haunt the BJP, although the national opposition is too weak and divided to capitalize on this opportunity.

Another feature of Modi’s India is the diminishing of the country’s great institutions. During an earlier era, the Supreme Court and the Election Commission were fiercely independent and powerful symbols of India’s flourishing democracy. These two institutions, along with many others, have been neutered under Modi’s rule. While Supreme Court justices in the past have been legal luminaries who guarded their independence from the executive, many in the current crop are unabashed Modi supporters. In February, Justice Arun Mishra told an international judicial conference that Modi was an “internationally acclaimed visionary and a versatile genius who thinks globally and acts locally”.

Not to be outdone, the once proud Election Commission decided to proceed with state elections despite public-health warnings that “super-spreader” campaign rallies (many of them addressed by the prime minister) posed a grave risk. In early March, a lower court in the state of Tamil Nadu criticized the Election Commission for proceeding with the polls in the state. “Your institution is singularly responsible for the second wave of Covid-19,” the court pronounced in its ruling. “Your officers should be booked on murder charges.”

Another proud feature of democratic India, the media, has also been captured by the state with “commando channels” outdoing each other in their vehement defense of the prime minister and his government’s handling of the pandemic. Instead of focusing on the humanitarian tragedy, one national channel devoted primetime coverage last weekend to a discussion of the foreign media’s “biased” coverage of the health crisis. India fortunately still has pockets of independent media who have bravely covered the pandemic and thrown light on corners of the country’s crippled health system which Modi’s acolytes would rather remain suppressed.

The outcome of last week’s state elections points toward an alternative path for the opposition. In three of the four states which held elections, powerful regional parties prevailed over the BJP, signaling perhaps that it is this group of leaders who pose a significant political threat to Modi. National elections, however, are three years away and the BJP will hope that a forgiving (and forgetful) public may overlook its bungling when the economy returns to normal. There may well be a terrible twist which even Modi cannot control. Pandemics, just like natural disasters, leave behind deep social scars with unpredictable consequences for politics and even the most durable of politicians.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.