The much anticipated summit in August between Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in Beijing failed to resolve the long-running South China Sea dispute between the two nations. On the eve of the 35th ASEAN Summit in Thailand (from October 31 to November 4), regional security expert Renato Cruz De Castro of De La Salle University, Manila, argues that Duterte’s vow to insist to Xi that the 2016 arbitration ruling in Manila's favor was “final and binding” rang hollow: China is set to impose its own policies through the soon-to-be-negotiated Code of Conduct for the contested waters, which once concluded could presage a shift in the regional balance of power.

Xi (right) shows Duterte the way, August 2019: Could Manila’s soft-pedaling of its territorial dispute with Beijing lead to a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea that fits Chinese interests? (Credit: Presidential Communications Group, Office of the President of the Philippines)

Prior to his fifth official visit to China in August, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte announced that he would raise with his host, President Xi Jinping, the 2016 decision in Manila’s favor by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague that Beijing has no historical rights to resources within the area in the South China Sea falling within its claimed nine-dash territorial line. Duterte said he would use the ruling to assert his country’s maritime boundary under the United Nations Conference Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Halfway through his six-year term, the president reasoned that it was about time for him to take up the matter of what Manila calls the West Philippine Sea and that he could not accept China’s insistence on sovereignty over contested waters.

Duterte also declared that he would push for the early drafting and immediate adoption of the Code of Conduct (CoC) for the Parties in the South China Sea dispute, which China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreed to work on 17 years ago. Conclusion of the CoC – impeded due to Beijing’s delaying tactics, Southeast Asian claimants allege – would reduce tension and minimize the risk of conflict due to an incident or miscalculation, the Philippine president promised. He wants to fast-track the COC because he does not want “trouble” for the Philippines. His efforts to prod Beijing came on the heels of the ramming of a Philippine fishing boat by a Chinese vessel in the Reed Bank and a protest by Manila to Beijing over the passage of several Chinese warships through the Sibutu Strait.

The Philippine leader’s pre-trip pledge built up expectations for the summit, which in the end produced only modest results. Duterte had said that he would be steadfast in his approach to Xi and would declare that the PCA decision was “final, binding, and not subject to appeal”. But in the moment, he found himself paralyzed when Xi reiterated China’s position of ignoring not just the ruling but the entire arbitral proceeding. Duterte retreated, later undertaking that he would not bring up the arbitration case with the Chinese president in future meetings.

He did agree to continue dialogue with China and to work with other ASEAN member nations and the Chinese to complete the CoC by 2022. Duterte emphasized the futility of confronting Beijing, opting to focus on regularly scheduled bilateral consultation. The Philippines is the ASEAN member responsible for coordinating the organization’s relations with dialogue partner China until 2021.

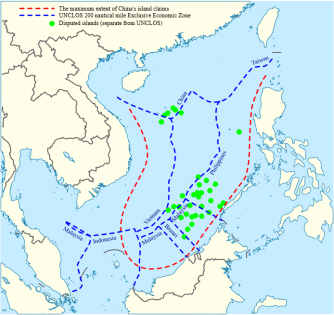

Competing territorial claims in the South China Sea (Credit: Goran tek-en)

Quest for a code of conduct

The idea of an ASEAN-China COC originated on September 2, 2002, after the two parties signed the “Declaration on a Code of Conduct (DOC) for the South China Sea”. The DOC was primarily a political statement of broad principles of behavior aimed at stabilizing the situation in the South China Sea and preventing accidental conflicts. ASEAN’s goal has been to transform the DOC from a broad statement of principles into a legally binding CoC.

All these many years later, the two parties have still not started actual negotiations for the CoC because China declared that it was not yet time to do so. On May 18, 2017, China and the 10 ASEAN member states suddenly announced that they had finally agreed on a framework for a CoC, with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi saying he would like to wrap up deliberations.

On August 6, 2017, ASEAN and Chinese foreign ministers endorsed the framework for the CoC negotiations. Their agreement was a small step forward in putting in place a conflict-management mechanism to prevent any escalation of the South China Sea dispute. The agreed framework, however, was short on details and contained many of the principles and provisions already mentioned in the 2002 DOC.

ASEAN insists that the COC must be legally binding. However, Beijing wants compliance to be voluntary, like the 2002 DOC. Furthermore, although the framework includes new references to the prevention and management of incidents, the phrase “legally binding” is absent from the text, along with any mention of geographical scope and mechanisms for enforcement and arbitration. The actual talks to draft the CoC are expected to be tough and protracted.

The framework agreement excludes the US and Japan, which are regarded as external actors that may “interfere” and marginalize ASEAN’s position in the South China Sea dispute. It refers only to the six Southeast Asian states’ claims against China’s. It frames the future negotiations for the CoC as strictly an issue between China and the ASEAN claimants.

Fast-tracking China's ambitions?

While Duterte committed his country to pursuing early adoption of the CoC, Xi stressed that joint efforts for an early conclusion should “exclude external disturbances in order to focus on cooperation and developments to safeguard regional peace and stability”. This appeared to signal that the CoC that could be negotiated by 2022 (by that time, Myanmar will have taken over as the ASEAN coordinator member for China) will be different from what ASEAN envisioned in 2002. This begs the question of how much teeth the rules will have – whether the rules and norms that will be set out will have any binding effect under international law or any dispute settlement mechanism.

ASEAN’s original goal was to negotiate a CoC that would enable the member states to apply a soft balancing approach on China in the region, bolstering ASEAN’s centrality or pivotal position in the Asia-Pacific region. The CoC that will be drafted, however, will probably contain provisions that will enable China to assume a regional leadership role, eclipsing ASEAN or essentially diminishing its longstanding and fundamental position as a fulcrum for the balance of power. It could also rule out the involvement of any countries outside of the region in the territorial dispute. Such an agreement would eventually allow Beijing to establish a Sino-centric regional order in Southeast Asia. If that comes to pass, the Philippines, under the Duterte administration, which itself runs till the middle of 2022, will have played a pivotal role in enabling China to achieve its goals and ambitions.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.